by Gary Singh

Only in Trieste could I visit a foreign consulate’s grave and come away feeling like an international diplomat.

To begin, I boarded the #10 bus in front of Caffè Tommaseo which took me to the Sant’Anna Cemetery. I did not bring any travel guides with me. Instead, I consulted a beautifully arcane source, the January, 1966, issue of Foreign Service Journal, a publication for Washington, D.C.’s foreign policy establishment, ambassadors and their families.

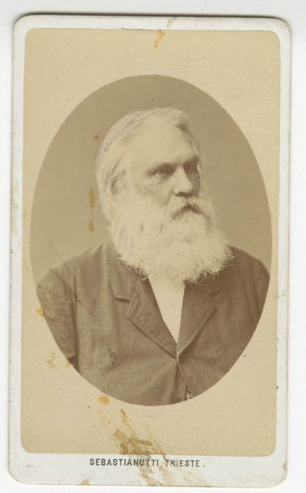

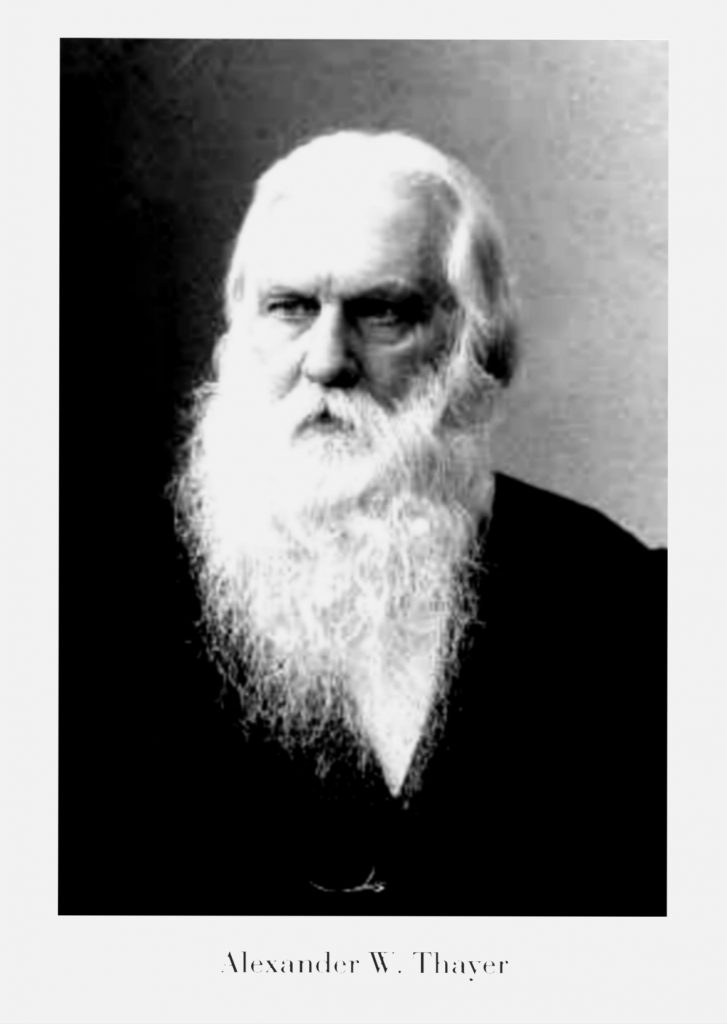

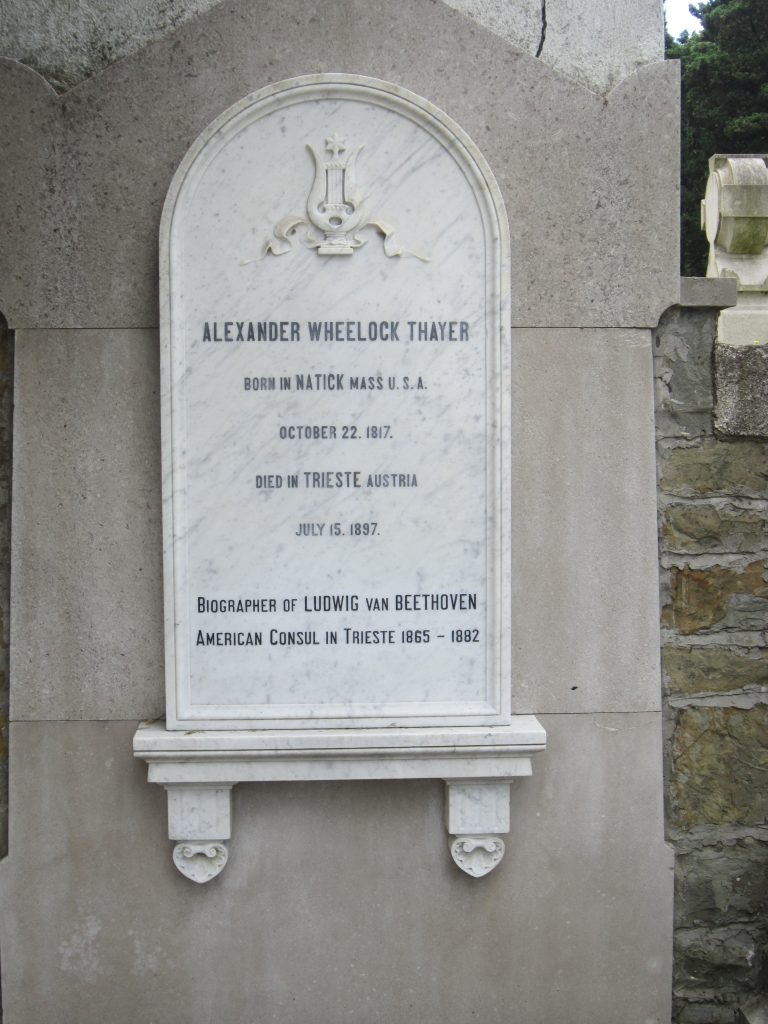

Within its pages I had discovered the heroic adventure of an American consulate staff member in Trieste that went looking for the grave of Alexander Wheelock Thayer (1817-1897), who was buried here. Back in the nineteenth century, Thayer wrote the first successful biography of composer Ludwig van Beethoven, working on much of the book while serving as the U.S. consulate in Trieste.

I wanted to get some photos of Thayer’s grave for a Beethoven research archive back home in Northern California. At the time, no modern-day shots of the headstone existed anywhere, so they asked me to visit his grave during my trip and I told them I would try.

So there I was, on the #10 bus, heading up Via dell’Istria. It was late in the afternoon and I had to fly back the following morning.

Born in Massachusetts, Alexander Wheelock Thayer graduated with three Harvard degrees before deciding to fully investigate Beethoven’s life. In 1840, when Thayer was in his early twenties, Anton Schindler published his own German-language biography of Beethoven, riddled with what Thayer already knew to be inaccuracies, so Thayer wanted to set the record straight and produce a more scholarly work. He moved to Europe, became fluent in German and spent many years in Austria, where his foreign service career also began.

By the time Abraham Lincoln appointed Thayer to the American diplomatic mission in Trieste, a post he started on January 1, 1865 and held for almost 18 years, Thayer was already obsessed with Beethoven. Even though Thayer wrote his book in English, it was translated into German and published in that language first. It was not published in English until decades after Thayer died.

By the mid-1960s, Thayer’s grave had been totally forgotten, so John P. Sabec, a former staff member at the American Consulate in Trieste, went looking for it, reporting on his adventure in the pages of Foreign Service Journal. At first Sabec looked through the small Anglican Cemetery where a previous local history book had incorrectly claimed Thayer was buried. Sabec and his accomplice scoured the cemetery, cutting thick ivy stems from various places to see which particular tombstones were covered up.

After more research, Sabec discovered that Thayer’s tomb was hidden away in the Evangelical Cemetery of the Augsburg and Helvetica Confession, where it was built into a retaining wall, covered in ivy. Nobody had maintained the gravestone and the debt for the plot had not been paid off in years, so Sabec tracked down Thayer’s descendants and straightened out the whole affair, which led to a good cleaning and repairing of the gravestone. We’ll never know for sure, but Sabec’s efforts may have saved the headstone from being discarded.

After stepping off the #10 bus, I had no idea where to go. The Evangelical Cemetery of the Augsburg and Helvetica Confession was one of several older contiguous sections adjoining each other at progressively lower levels as they descended down a hillside, some of which were accessible from Via della Pace, the road separating them from the main ground, the Sant’Anna Cemetery. Unfortunately, when I arrived late in the afternoon, the Evangelical section was closed. A set of gigantic medieval-looking doors opened into the cemetery from Via dell’Istria, but they were padlocked shut.

The military section was the closest open area, located on the next upper level, so I walked in from Via della Pace and spent a few minutes trying to figure out a way to sneak into the evangelical section, if that was even possible. It wasn’t.

After a few minutes, I walked back out toward the road, where I spotted a woman watering some flowers on the side of a large embankment. I shuffled up and handed Maria Neva Micheli the paperwork I had on Thayer, including his photograph. Between her English and my broken Italian, we were able to communicate. She directed me to a parking lot outside, where her husband, Loris Guarini, was sitting in a tiny red car. They were both kind enough to drive me all the way around the entire graveyard complex to the main entrance so we could inquire at the front office. I could barely fit into the back seat.

Unfortunately, we learned from the main office that if the doors to the Evangelical Cemetery were indeed shut, there was nothing anyone could do. The folks with the keys would not return until the following afternoon. I was out of luck.

In a gracious act of hospitality, Maria then wrote down my email and said she would come back to the Evangelical Cemetery the next day, take photos and send them to me. I gushed with thank-yous, and we both said ciao, arrivederci.

Two days after I returned home to California, an email arrived from Maria. Attached were several photos of Alexander Wheelock Thayer’s grave, in all its glory. I relayed them to the Beethoven research facility, who said the photos would be included in a future exhibit.

Even though I never got a chance to see the grave in person, I felt a tremendous sense of foreign service, thanks to John P. Sabec, and the Triestine diplomacy of Maria Neva Micheli, my local intermediary. I felt like an international diplomat. My mission was complete.