by Gary Singh

At its creative best, travel merges a physical journey with a bibliographic journey, encouraging the literary pilgrim to improve his book collection and continue the quest. In Trieste, I did not want a conventional guidebook, so I instead turned to authors like Scipio Slataper (1888-1915) and the contemporary maestro Claudio Magris. They became my lampposts, illuminating a journey through past and present.

I already considered Slataper a creative ancestor worthy of serious homage after I ingested a recent English translation, My Karst and My City and Other Essays. The book, including a mammoth 70-page introduction by Elena Coda, titled, “This Little Corner of Europe: Slataper’s Reflections on and around Trieste’s Cultural and National Identity,” is the most comprehensive English-language study on Slataper to date, a glorious presentation of the man and his time.

In 1909, writing in the Florentine literary magazine La Voce, Slataper penned “Lettere triestine,” a series of “letters” in which he attacked Trieste’s apathetic reluctance to embrace its own transnational condition. Trieste was a multi-ethnic, multilingual kind of place, where a homogeneous identity couldn’t possibly occur. Many longed to unite with Italy, yet they couldn’t completely give up ties to Austria. Tension raged between Italian nationalists and Slav nationalists, all while the language of higher literary education was German.

Sick of watching society suffer, Slataper encouraged the citizenry to embrace the ambiguity of their condition. He argued for a new literary identity borne from its own contradictory nature. If the populace could accept the radical multiplicity of Trieste, then a new literary sensibility would blossom.

“This is Trieste. Composed of tragedy,” he wrote. “In sacrificing the possibility of a straightforward existence, Trieste gains her own anxious originality. We must sacrifice our peace in order to give it expression. But express it we must.”

The Triestine soul was different. All its contradictions could not be reduced to a singular frame of mind.

“Trieste has a Triestine type,” wrote Slataper. “It must strive for a Triestine art capable of reproducing, through joyful clear expression, our fragmented and difficult existence.”

Three years later, his major achievement, Il mio Carso, a fictionalized lyrical autobiography, explored multiple dimensions of Trieste—past and present; Italian, Austrian and Slovene; city and countryside; wilderness and ghetto—allowing Slataper to merge his own fractured sense of self with that of Trieste. Via fragmentary narrative techniques, the protagonist realized his true nature by refusing any attachment to a fixed identity while Trieste emerged as a city that embraced its own contradictions and thus directed the protagonist toward inner peace.

Sadly, Slataper’s real life was cut drastically short and did not end in a peaceful fashion. After volunteering to join the Italian army in World War One, he was killed during the Fourth Battle of the Isonzo in December of 1915. He would write no more books.

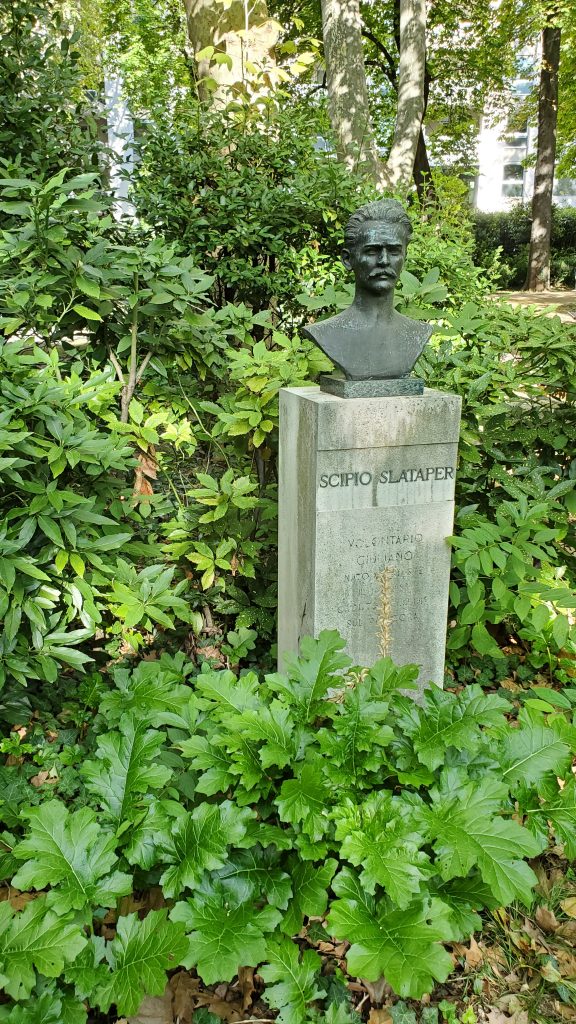

In today’s Trieste, the most serene place to contemplate Slataper was Giardino Pubblico Muzio de Tommasini, commonly referred to as the Public Garden. Shaped like a giant triangle and filled with elms, oaks, cedar, ginkgo and several other species, the park featured various gray busts of famous local writers on concrete pedestals, each one emerging peacefully from the warm green shadows. James Joyce, Italo Svevo and Slataper were among them.

I visited the garden more than once. Not just a testimonial to the city’s literary heritage, the garden was also the setting for an entire chapter of Claudio Magris’ 1999 book, Microcosms—required reading for any imaginative traveler that wants to reflect on his life while in Trieste.

In Microcosms, the anonymous narrator reflects on elements of his own story—characters, historical events and regular haunts—while fusing them with the city’s life story. The real and the symbolic merge together in masterful fashion.

Chapter Eight finds the narrator in the Public Garden. His appraisal of the Slataper statue percolates with melancholy. Unlike the rest of the statues, the bust didn’t even say that Slataper was a writer of any sort. It just mentioned his medal from the war. Apparently, his sacrifice was more important than how he spawned an entire century of Triestine literary dynamism.

“Busts are not appropriate for Slataper and his generation,” writes the narrator of Microcosms, “but they are the sad truth of that generation that was burned out in its green youth.”

Slataper envisioned and imagined a vibrant Trieste culture. He wanted to destroy the drab grayness of the world and venture forth into the greenery of a better life. Now he was relegated to a gray statue in a green public garden. The narrator continued:

“Slataper’s generation created Triesteness by denouncing the reassuring busts, the museum of traditional and systemic knowledge that makes for rigidity and eludes the drama of existence, inserting and neutralizing all phenomena in catalogues and classifications.”

Unlike Joyce, Slataper’s output wasn’t monumental enough to take over the world and become the subject of literary journals, museums and international conferences. He never grew old enough to become a historian of local literature passing down knowledge to others, like Magris or his narrator.

As a result, we have Slataper’s youthful screeds and that’s all we have. At 27 years of age, he left a lifetime of contradictions. As a literary pilgrim, all I could do was continue to pay homage.

Enjoyed learning more about the literary and past history of la mia Trieste, my birth city. Will always long to be reunited.