By Alessandra Ressa

On May 2nd 1974 at 11.12 p.m. Trieste’s fire department received an emergency call. Smoke was coming out of a storehouse in via San Maurizio 13. A few minutes later, the firefighters managed to break through the main door of the building. The whole storehouse was by then engulfed in tall flames.

As the firefighters were attempting to extinguish the blaze, they weren’t aware that at in a small room next to the depot there was a man. As soon as the fire was put out, among the crowds of curious residents and journalists, investigators armed with flashlights proceeded to inspect the storehouse.

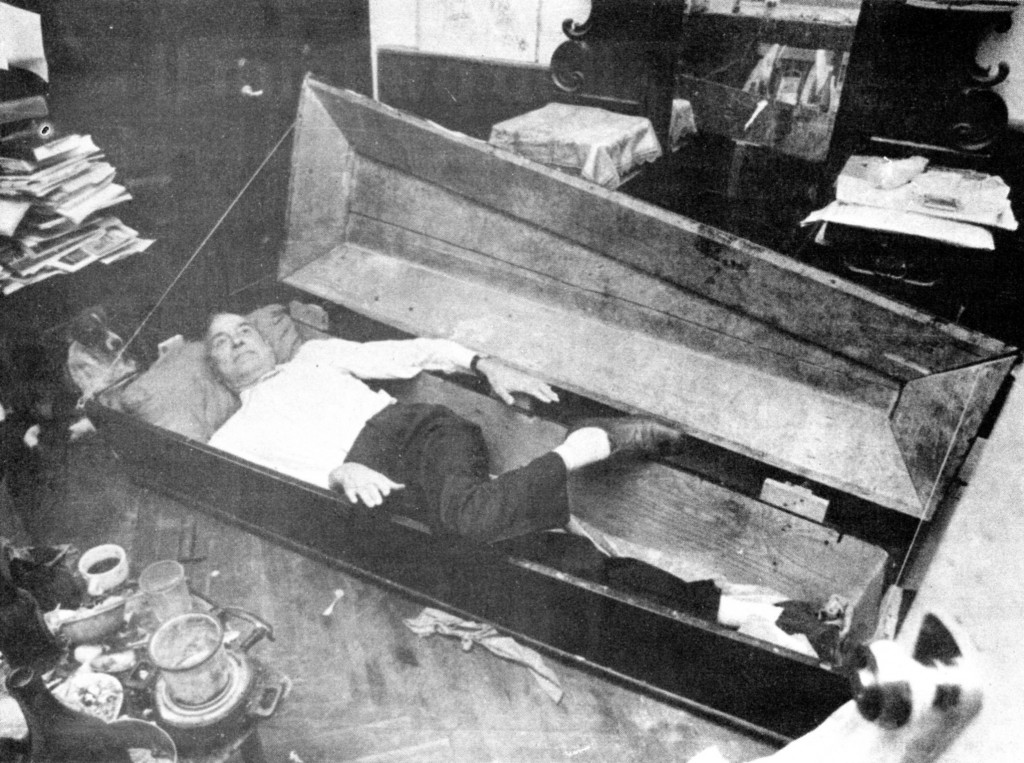

Amid foul smells and blackened piles of materials of all kinds, they found the charred remains of the man who lived in those storage rooms. It was Trieste’s historian and eccentric collector Diego de Henriquez. The body was found inside an open casket.

The case was inexplicably closed soon after the tragedy. The investigation quickly concluded that Diego de Henriquez had died in an accidental fire, in which a large part of his precious historical military collections, including many original documents and photographs witnessing the events in Trieste during World War II, went up in smoke.

AS bizarre as it sounded, his family explained to the police that he had taken to sleeping in a casket lately. He also wore a heavy German helmet on his head and a Japanese samurai mask on his face “so that – he was quoted – my thoughts will stay preserved in my head while I sleep”.

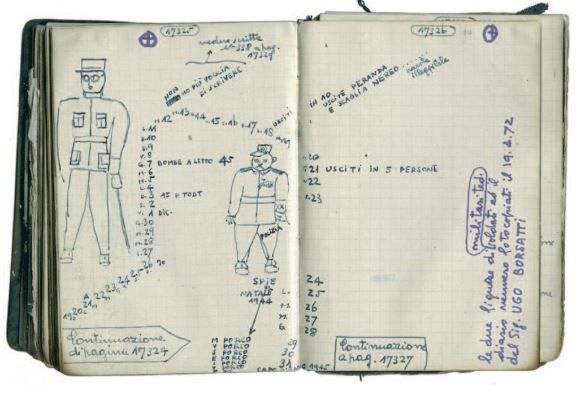

The storage-museum of via San Maurizio had been robbed several times before the fire – a fact that triggered the curiosity of local journalists. In particular, according to several witnesses, de Henriquez kept diaries – hundreds of them- in which he obsessively reported everything he saw and heard during and after WWII.

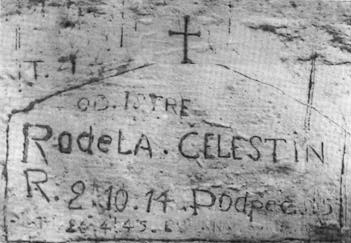

In some of these diaries, kept in via San Maurizio, he allegedly copied word by word the messages scratched on the walls of the tiny cells of the infamous Risiera di San Sabba, the former rice mill used as a concentration and extermination camp during WWII in Trieste.

As he was allowed access to the cells immediately after the liberation in 1945, he proceeded to jot down over 600 messages he found on the walls and even reproduced drawings.There were the names of the victims – mostly Trieste Jews, Italian, Slovenian and Croatian partisans.

In addition to personal information, according to witnesses who knew about the diaries, the graffiti profusely named those Trieste collaborators who had betrayed, reported, arrested and tortured the prisoners.

Soon after the liberation, hurried local authorities proceeded to cover in plaster the walls of those cells. De Henriquez often spoke about the content of his diaries with friends, adding that several of the names he had copied belonged to prominent citizens who occupied important positions after the war. After the fire, although many of his journals survived the flames, those specific diaries disappeared.

Coincidentally (or not), at the time of his death, public prosecutor Sergio Serbo was investigating crimes committed by Triestini in the Risiera concentration camp during the fascist regime and Nazi occupation. De Henriquez’ death must have been quite a relief for those implicated in the crimes whose names had been written on the Risiera’s walls. The family, friends and the public opinion began to pressure for further investigation.

De Henriquez’ death began to appear suspicious to prosecutor Gianfranco Fermo, who declared that “it was a mistake to not immediately order an autopsy. I have a feeling something might have escaped the investigation”.

Six months after his death, the first autopsy was eventually performed. But it was too late to find any signs of violent death as the body was too decomposed. The coroner found pieces of copper wires mixed with the remains, but at that point it was impossible to determine if they had been used to tie the body.

The Carabinieri who carried forward the second investigation assumed that someone had entered the storehouse with the purpose of stealing but was caught in the act by de Henriquez. He was consequently killed and the fire was started to eliminate any trace of the crime.

Before the tragedy, the collector told friends he was visited by suspicious people, allegedly interested in buying some of his objects. He confessed that he felt he was in danger, and started carrying a loaded gun wherever he went. Although this information was passed on to the prosecutor, the case was eventually closed. The mystery of his death has not been solved to this day.

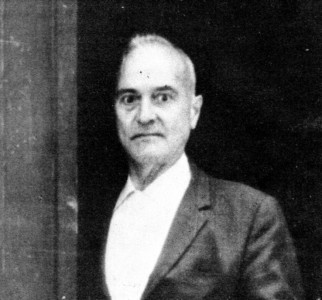

But who was Diego de Henriquez? Born in 1909, he spoke 13 languages fluently. Because of his vast knowledge of history he was known to everybody in Trieste as the professor.

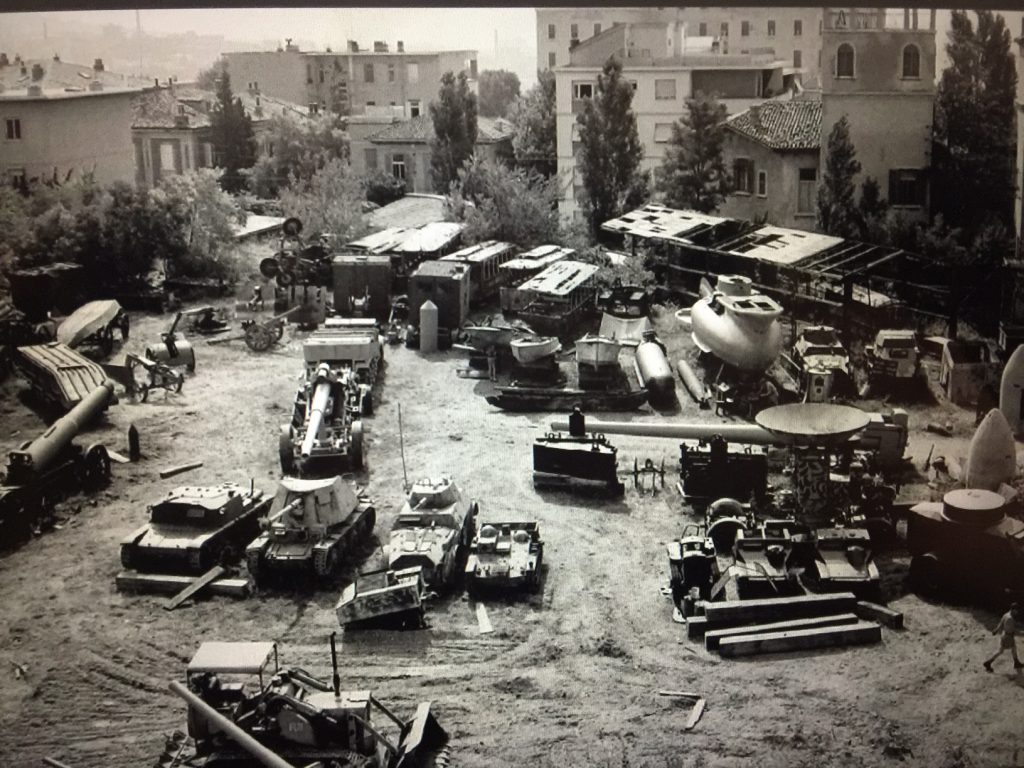

During and after WWII he collected military antiquities of every sort. From uniforms to tanks, from cannons to submarines. Paying out of his own pocket, he was able to assemble an immense array of military artifacts.

His passion soon became an obsession. He explained that he had inherited it from his family ancestors who, he claimed, had fought in the Crusades, in the Napoleonic Wars, and in the two World Wars.

His dream was to create the biggest war museum in the world right here in Trieste. As de Henriquez often explained, it was to become a war museum to remind us of the importance of peace. He was arrested 18 times for being in restricted military areas trying to negotiate pieces for his future museum.

His collection became so big and bulky that the Trieste municipality reluctantly assigned to him dismissed army barracks and various spread-out warehouses to store it. While he waited for a permanent location where to finalize his museum, and while he hoped for the much-promised financial support from the local administration, his stuff was often moved from place to place due to the out-of-control apartment-building frenzy of the post-war years.

During the moves many vehicles got damaged beyond repair, others had to be sold to support himself and his family, and to pay for maintenance of his remaining treasures while waiting for government funds. There was a bare hill in San Vito (now replaced by buildings) where he kept many of the vehicles parked in the open. Children from the neighborhood used to love to spend their time in the temporary outdoor museum, climbing tanks and cannons, in the company of this educated if eccentric gentleman.

De Henriquez’s enormous financial sacrifices eventually left him and his family penniless. He had to sell all his properties, as well as some of the most precious pieces of his collection, and abandon others for lack of space.

The Trieste public administration demonstrated little interest in supporting his museum and his financial situation reduced him to a state of depression and mental instability until his death.

Only in March 1997 his collections were annexed to Civici Musei di Storia e d’Arte di Trieste. Soon they became the Municipal Museum of War for Peace Diego de Henriquez.

In 1999 the museum moved to the decommissioned army barracks in via Cumano 24, where it officially opened to the public on June 23, 2000. It took more than 60 years to achieve his dream.

The museum has a rich military collection that leads you through unique objects and photographs of the history of Trieste during the two World Wars. It is a jewel that still feels a bit neglected by the Trieste public administration, but more than worth a long visit despite the decentralized location.

Trieste’s writer Claudio Magris dedicated his bestselling novel Non luogo a procedere ( English title: Blameless) to Diego de Henriquez. In his novel, which takes place during and after WWII, a war memorabilia Trieste collector is at the center of the story, which, step by step, develops into a beautiful partially historical, partially fictional narrative entirely set in Trieste. The title, Non luogo a procedere (literally “no further action”) refers to the trials for the crimes committed at Risiera di San Sabba, for which many of the accused were released for lack of evidence.

If Trieste municipality wasn’t able to recognize the genius and the enormous value of the work of Diego de Henriquez while he was alive, it is not any better today. Even if he has been publicly acclaimed as one of the city’s most popular and selfless benefactors, a quick stroll in Sant’Anna’s former military cemetery will break your heart once you approach his grave.

The stones have partially collapsed, some of the decorations have been removed and thrown to the side, a white and red chain admonishes the visitor that the grave is unstable, do not go near! The pitiful, precarious condition of the grave of Diego de Henriquez is yet another, posthumous blow to this generous man who contributed so much to Trieste’s history.

Veit Heinichen’s book “Le lunghe ombre della morte” also tells the “story” of Diego Henriquez and his mysterious death – in a detective noir novel…