words :Alessandra Ressa

Illustration: Olha Polonska

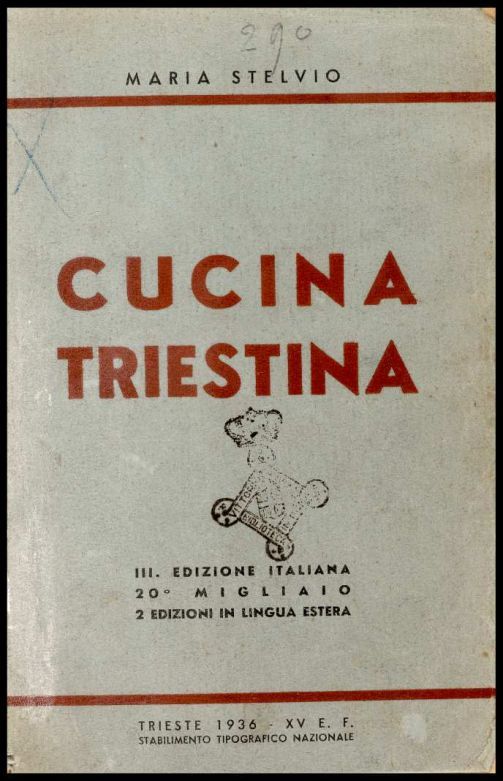

A cookbook written in Trieste almost one hundred years ago could ensure good and affordable food on our table in the fall and winter months ahead. Written in 1927 and re-edited in 1942 and 1945 during World War Two, when the worse fuel and economic crisis hit Trieste, Cucina Triestina by Maria Stelvio may be the answer to simple, tasty, inexpensive food in times of emergency like the one we may be about to experience.

Today Maria Stelvio is mainly known in Trieste for her popular cookbook, but she was not the typical woman of her time. While most upper class Triestini were content with being wives and mothers, Maria, born in the late 1800s, when the Austrian empire dominated the city economically and culturally, began her career as a teacher and later became a journalist and a war correspondent. She fearlessly wrote dispatches from the Piave front during the Great War. Back in Trieste, she became passionate about cooking and began collecting traditional local recipes.

In 1927, with the wedding day of her eldest daughter approaching and worried that the young woman may disappoint her husband with her limited experience in the kitchen, Maria decided to give her daughter a very special gift, a simple, unpretentious cookbook that could be handled successfully even by the most dreadful of cooks. In the preface of her popular work you can read her dedication, not only to her daughter, but to all the young women who were expected to give up their professional life for the sake of raising a family. After all, it was the beginning of fascism in Italy, where propaganda and gender discrimination put great pressure on women who wanted to have a career outside the household.

The next updated edition of Cucina Triestina was published in 1942. War was full-scale all over Europe and Triestini lived in a daily fear of bomb raids by the Allied forces. Food was rationed, people had to stand in day-long lines to get flour and other basics which were usually not enough to feed the whole family. Fuel for cooking was scarce. On top of that, fall and winter were particularly cold that year, while supplies of coal, wood and gas were rare, making it difficult to keep warm at home. The 1942 edition, full of tips on how to economize on food, how to reuse leftovers and scraps for unexpectedly good meals, but also how to save on gas and heating as well as how to keep warm with simple, energetic recipes was inevitably a great success.

The main thing to save, Maria explained, is cooking gas, coal or wood. It greatly helps to pile the pots one on top of the other so that there is no heat dispersion and more meals can be cooked at the same time over the same fire. Among the many ingenious tips to save on fuel was “homemade wood”, obtained by soaking, pressing and drying food-wrapping paper. The book is full of incredibly witty tips, many of which no longer applicable in the modern kitchen but certainly worth reading.

The recipes in the cookbook are quite a treat, as they combine old Trieste cooking traditions with foreign, and particularly Austrian, contaminations. A recipe that is particularly popular in the book because of its simple, inexpensive and nutritious ingredients is Koch de Gries, a mix of Triestino and German words that simply mean cooked semolina.

This delicious soft cake, typical of the month of October, has almost been forgotten today, very rarely will a fancy restaurant list it in its menu, but the elderly in Trieste remember it with great nostalgia. “It required planning and family participation – remembers Nadia Stancic, 88 – I was 10 years old in 1944 and my grandmother would send me and my two younger brothers into the woods of Cattinara to pick pine nuts from the pinecones that had fell on the ground. I remember that there were many people gathering wood and picking pine nuts like us. We had to be really careful not to smash the nut when trying to break the shell with a stone.” Nadia’s mother had stood in line for hours with the ration card in her hands to get eggs, sugar, milk, butter and semolina and when the children came home there was a wonderful feeling of joy and great expectation for what was to come out of grandma’s wooden oven at the end of the day. “We felt it was Christmas every time my grandmother told us to go and get pine nuts. In the cupboard, we had a jar full of raisins that no one was allowed to touch. I remember the whole cupboard pleasantly smelling of raisins. I felt extremely privileged every time grandma asked me to pick a handful and soak them in water. No sta magnarli cussì, don’t eat them, she would always warn”.

According to Maria Stelvio’s recipe, to make this delicious dessert you need 1 liter milk, 250 grams semolina, 80 grams butter, 4 eggs, 120 grams sugar, 1 whole lemon peel grated, 20 grams raisins and 20 grams pine nuts. Bring the milk to a gentle boil then add the semolina flour little by little. Add a pinch of salt and the grated lemon peel. Stir until thick. Remove from fire, add sugar and butter and stir until sugar melts. Let it cool down. Separate the yolks from the egg whites and beat the egg whites. When cool, add the yolks, raisins and pine nuts (leave some nuts to decorate the surface) then gently add the firm egg whites. Grease a baking tray and pour the batter. Add the pine nuts. Preheat the oven at 180° C and bake for about 45 minutes to 1 hour.

“I remember the wonderful smell of this cake in our little apartment – Nadia recollects – and how reassuring it was to hold it in our hands, this cake was our little personal happy corner at a time of great fear and insecurity. We usually ate it warm and it kept us happy till morning when we could get another little slice before school.”

Cucina Triestina was so successful that it was reprinted periodically for almost a century. Each edition contained new tips and adjustments to keep up with time, historical and social changes. Unfortunately, it has never been translated into English.

Alessandra,

Grazie tanto per questo “review” del libro “cucina Triestina”…

La mia mamma viene da Gorizia, ed a l’alta età di 89 e proprio del generazione fortissimo, ma molto dura. Tutta la mia vita la mia mamma ha usato il libro CT. Cercavo proprio per CT English version, ma vedo che non e stato traduito in Inglese. Ormai!

Grazie tanto, Luisa