By Alessandra Ressa

Bread has been a beloved primary source of staple in the Western world since the beginning of time and it is often the symbol of a national identity. Think baguettes in France, pretzels in Germany, pizza and focaccia in Italy, pitas in Greece and the Middle East, dark rye bread in Finland, naan in India, arepas in Venezuela, cheese buns in Brazil, corn bread in the United States – just to name a few. Even Japan has recently developed its own type of curry bread – a very popular fried bun filled with curry sauce.

You don’t need to be a bread addict like myself to appreciate and marvel at the fragrance, the texture, the beautiful, comforting shape of bread. But what’s even more impressive is the story behind each of these divine creations. Especially the Servolane bread in Trieste.

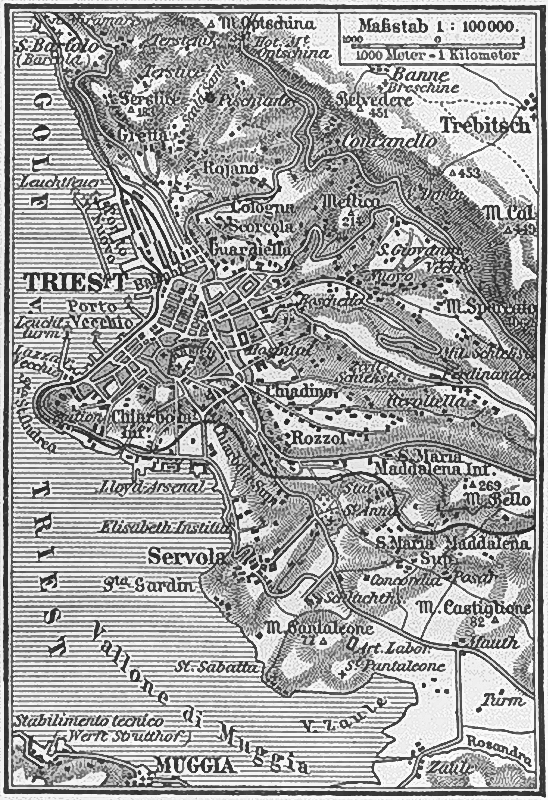

Servolane is a distinct type of bread that has been baked by women in Trieste for the past 500 years. As its name reveals, it comes from the old Servola neighborhood, now an overpopulated and polluted area of town.

Before it became an industrial settlement, Servola was a charming village with little farm two-story houses clinging to the top of the hill, surrounded by woods and pastures.

Triestino gentlemen, intellectuals and townsfolk in general, loved to take the tram up to Servola village where they bought its famous bread and strolled in the countryside. They would then sit on the hilly slopes overlooking the sea and eat it while still warm.

Trieste writer Italo Svevo was one such connoisseur, as from his famous novel Zeno’s conscience (a must read if you live in Trieste).

Servolane buns were considered the most genuine and traditional breads and were made by a group of specialized women bakers, often from the Slovenian minority, known as pancogole – from Latin “panicocula”, – literally “woman who cooks bread”.

Not only did they bake this very special bread at home, but they also carried it in baskets on top of their heads and walked all the way to Trieste to sell it.

Trieste’s upper and middle classes loved Servolane bread and lined up to buy it in the main town squares. Baking bread at home for many women was a way of making ends meet while men were in the fields. At the time bread from bakeries was expensive and of poor quality.

The first official source to report and regulate the activity of pancogole was a municipal statute from 1589. The women had to make an oath in front of magistrates. They swore they would carry out their trade “with diligence and honesty” and that they would buy the flour for Servolane solely at the public municipal deposit. This ensured the municipality got good money from the business.

The public municipal flour, however, was dirty, ill preserved and very expensive. In 1710 Servola representatives protested, but to no avail. In 1741 more restrictions were applied to Servola’s pancogole. They could access the city center only through the Cappuccini door in Cavana. They were also limited to sell their bread in Via del Pane in Città Vecchia (thus the name).

Authorities often confiscated the bread for futile reasons thus making life uneasy for these women. But their hard work finally received the deserved recognition when their reputation reached the highest spheres of the Austrian Empire. The pancogole were invited to court in Vienna in 1756 and 1764 to teach Austrian bakers to make Servolane.

During the following years, local authorities and official bakers attempted to limit the competition of pancogole, but these unstoppable women always managed to find ways to sell their delicious bread, often illegally, throughout town.

In 1921 the municipality of Trieste tried to regulate the activity forcing the women to buy expensive licenses in order to work. A license cost 500 lire, an enormous amount of money then, approximately 50,000 euros today.

During the two World Wars selling bread in the streets was against the law, and several non-complying pancogole were jailed.

After World War II, during the 9 years of Allied Military government licenses became more affordable, but that unfortunately didn’t last long. When Trieste became part of the Italian territory once again, new expensive requirements were introduced and many pancogole gave up their trade.

Slowly, these home bakers began to disappear: there were only twenty of them left between 1955 and 1972, when the last pancogola officially went out of business.

Two areas of town still remind us of this ancient tradition, one is Via del Pane in Città Vecchia, where urban Triestini could buy Servolane, and the other is Via del Pane Bianco, in Servola, where many home-made bakeries stood.

The pancogole are remembered in Servola each year with a special celebration where women wear traditional costumes. There is an ethnographic museum where you can learn a lot about the history of the village and its bread makers. Although it is not possible to buy the famous bread directly from pancogole today, you can find Servolane in many bakeries in Servola and in the city center.

Servolane are unfortunately not for vegetarians as they are made with lard. The great thing about them is that they stay soft and can be preserved for days. In my house, however, they never make it to the next day.

Great history!

I lived in via pane bianco, before I left the country, but I understand the street name via pane bianco has since changed., what is the current street name??

I visited 4 years ago but could not find it, so much has changed in the past 50 yrs.

Thank you for this historical piece, ervolane was indeed the best bread made, I can still asmell it, my Nonna was one of the baker in those days.

Luciana

Hi. Actually via del Pane Bianco still exists in Servola.

Actually via del Pane Bianco still exists in Servola.