by Alessandra Ressa

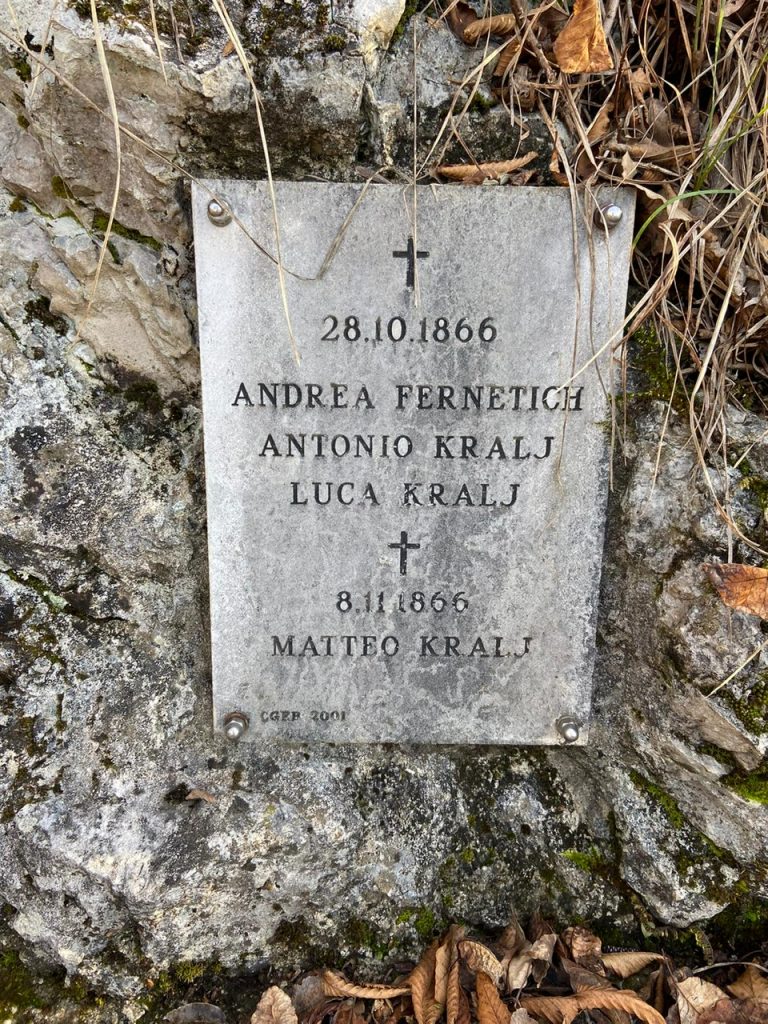

The tragic deaths of three members the Kralj family, Antonio, Luca, and Matteo, and of their fellow speleologist Andrea Fernetich, have been largely forgotten in Trieste. Today, only a sign placed in 2001 next to Trieste’s third deepest vertical cave, in which they lost their lives, is left to remind hikers of the ultimate sacrifice made by these municipal workers during the quest for water in Austro-Hungarian Trieste. The cave is known as the Pit of the Dead (Grotta dei Morti).

Scarcity of water had been a problem for centuries in Trieste. The economic boom and consequent population explosion in the mid-1800s made the situation worse. Although underground river Timavo had been discovered flowing at the bottom of the Abyss of Trebiciano cave, there still wasn’t enough water for drinking and agricultural purposes, especially in the overpopulated area of San Giovanni. Torrid summers were particularly hard for the residents.

In November 1861, Archduke Maximilian, who had settled permanently in Trieste, asked French abbot Richard, a renowned geologist and diviner, to investigate the path of the underground river in the hope that it flowed near the city. The abbot concluded that it was quite plausible that from Trebiciano it ran along the foot of Carso, not far from upper San Giovanni. Trieste’s municipality immediately financed new explorations in the area, beginning with a cave on Monte Spaccato. The cave was close to Trieste and already known for frequent air currents believed to be caused by underground water.

The cave was optimistically named Vent of Hope. It was an unknown recess and municipal teams of speleologists began its exploration in 1862. Among them 43-year old Luca Kralj, a farmer from the nearby village of Trebiciano. A little over a decade earlier, he had been the first speleologist to set foot in the Abyss of Trebiciano. He was a Grottenarbeiter (German word for cave worker), a unique profession at the time which played a fundamental role in cave geological research in Carso in the 1800s and early 1900s’.

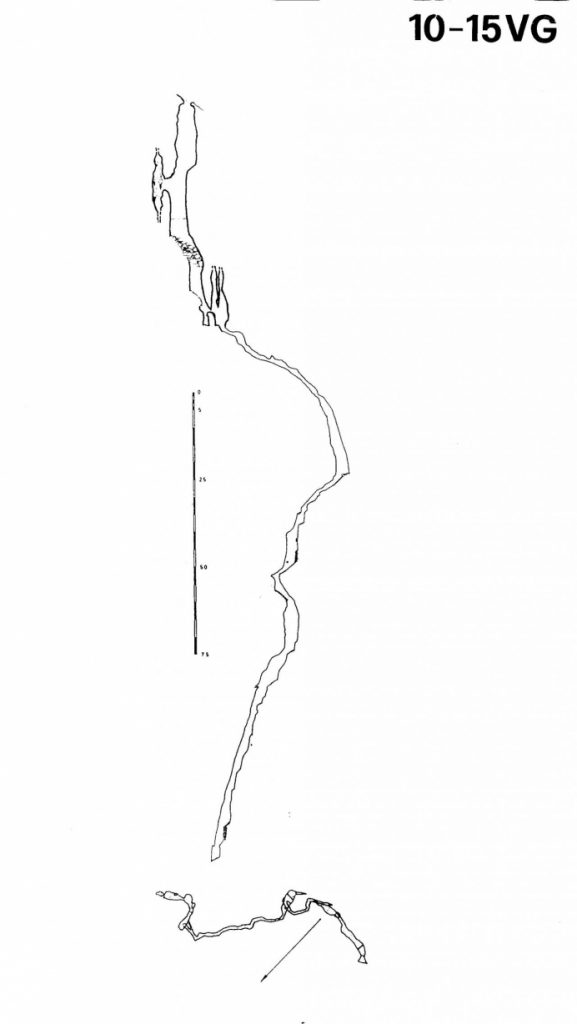

It was soon realized that the Vent of Hope was a narrow, deep and vertical pit. After one year of excavations, the workers were able to reach a depth of 243 meters. Particularly hard was the continuous removal of debris obstructing the progressive descent. Leather bags full of rocks and mud had to be constantly and manually pushed in and pulled out for hundreds of meters (the cave had several diagonal passages). Some debris was precariously left in the hollows of the cave and often slid down hazardously.

In addition, the deeper the Grottenarbeiters went, the less they were able to breath. There was little air circulating in the pit. When they reached 245 meters, the workers declared they could hear the faraway noise of dripping water and pulsing air currents. This, they believed, meant they were near a larger room, probably the bottom of the pit. They also believed that the bottom was filled with flowing water. This idea was reinforced by the fact that the gallery where they were digging had been flooded three times by water which, when reabsorbed, left a layer of sand. But, in May 1864, at the depth of 254 meters, the team had to admit that it had become impossible to proceed any further, as the little air in the pit wasn’t even enough to keep the oil lamps going.

Projects to improve ventilation were taking time, therefore another solution was considered. Blowing up the passage to widen it seemed the best, if extreme, way to go. After a whole year filled with various bureaucracies, on October 28th 1866, a mine containing over 400 Pfunds (a Hapsburg measure of weight) of explosive powder, approximately 200 kilos, was carefully lowered into the pit. The fuse was lit, and workers positioned all over the area waited for the explosion. But no noise was heard.

After 45 minutes, believing that the mine had not exploded and sure that the experiment had failed, Luca Kralj, his brother Antonio, and fellow Grottenarbeiter Andrea Fernetich volunteered to go down the pit to check. Worried by the fact that the three men were not re-emerging, two more men were lifted down. At a depth of 130 meters, they found the pit completely saturated with gas from the explosion while one of the three men lay lifeless down below. There was no trace of the other two.

An investigation followed and access to the pit was temporarily forbidden. However, ten days after the tragedy, on November 8th, five men lowered themselves down, in the unlikely hope to find the speleologists still alive, or, at least, to collect their bodies. Four of them were friends of the Kralj brothers from a nearby village (today’s Lokev, in Slovenia), the fifth was Matteo Kralj, whose father and uncle went missing ten days earlier. When they reached the depth of 70 meters they realized that the cavity was filled with gas. Matteo fainted immediately while the remaining four, after a vain attempt to carry the young man, were forced to leave him behind and miraculously managed to escape.

This second tragedy forced the municipality to abandon the project, the pit was closed with a large rock to avoid further accidents and the four bodies were left inside. The Vent of Hope became the Pit of the Dead. An attempt to recover the bodies was made 30 years later in1894 by a group of speleologists called Club Touristi Triestini. They managed to locate some of the remains, but local authorities didn’t allow the removal. They nevertheless left a sign of their passage that can still be seen today.

In 1957 another group of Trieste speleologists, Gruppo Grotte “Carlo Debeljak”, attempted to reach the bottom of Grotta dei Morti. It took them six months to remove over 80 tons of debris and mud. The bodies of the four workers however have never been recovered. Today, although much of the way down the cave has been secured by generations of speleologists and the pit can be visited by expert enthusiasts with proper equipment, the remaining 36 meters to the bottom still remain unexplored. You can find the cave along hiking trail 18, halfway between Sella di Banne and Sella di Monte Spaccato, a little off the path to

Good article, but not up to date. You mentioned cave groups that explored the cave in the 50s, but you missed out on the most recent explorations. The cave group which has worked recently in the “Grotta dei Morti” is Club Alpinistico Triestino (CAT). In 2016 they published a book “La Caverna sotto il Monte Spaccato. Da Foro della Speranza a grotta dei Morti. Centocinquanta anni di esplorazioni, tragedie e speranze speleologiche” by Daniela Perhinek, Maurizio Radacich and Moreno Tommasini. You can probably request the book at CAT headquarters, in via dell’Abro, Trieste.