by Alessandra Ressa

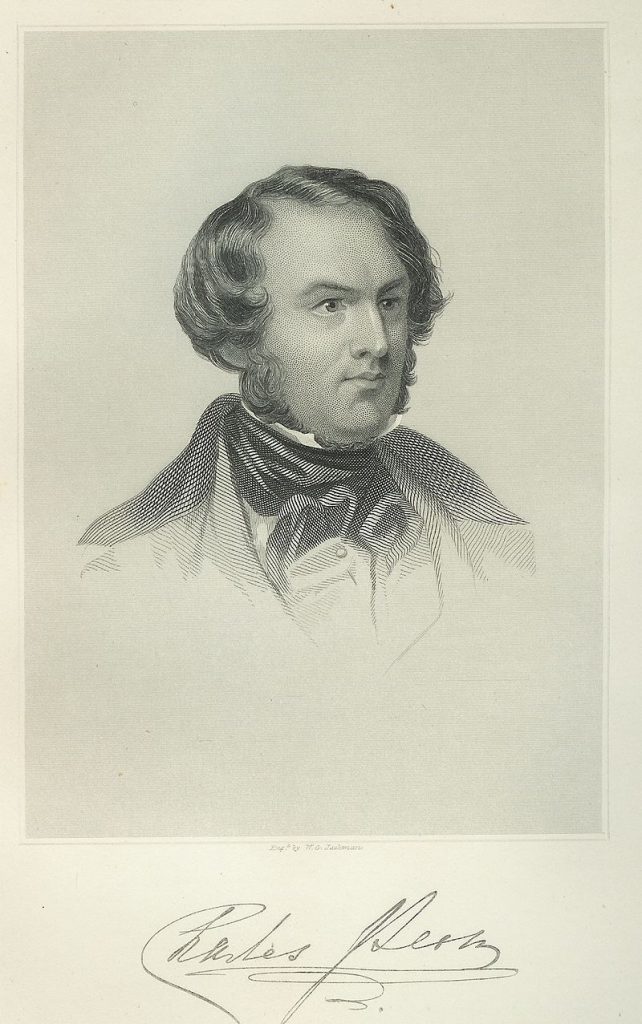

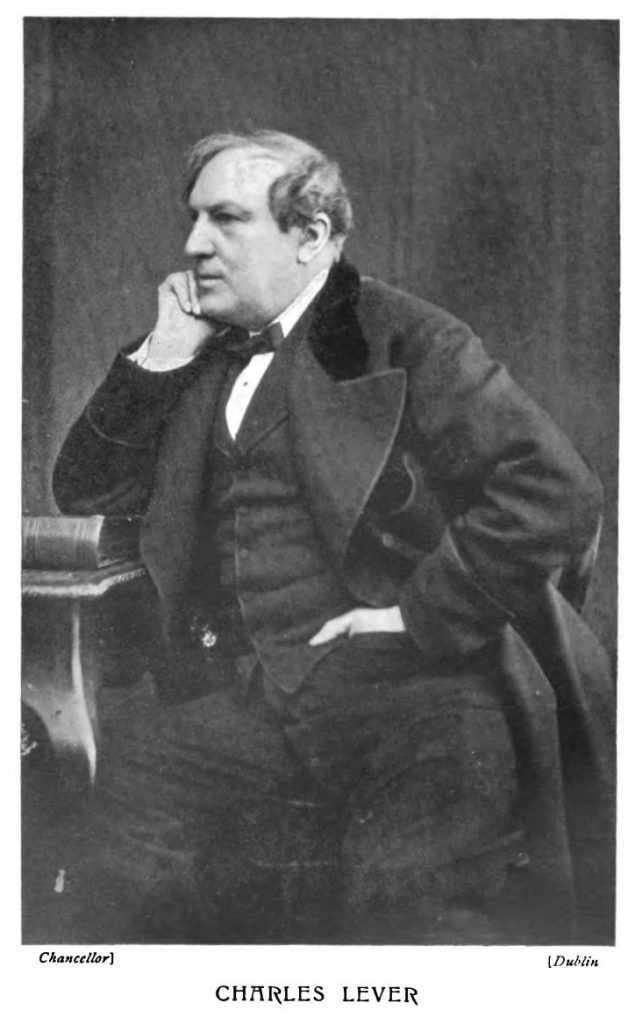

Everybody knows novelist James Joyce and his unique relationship with Trieste where he lived and worked for many years. But few people know that before Joyce even set his melancholic foot in town, a fellow Irish writer and surgeon, Charles James Lever, much admired by poet Anthony Trollope, found his late artistic inspiration in the city, where he lived like a Victorian gentleman of his time.

His novels, set in post-Napoleonic Ireland and Europe, featured lively, picaresque heroes inspired by his own life and travels. Appointed as British Consul in Austro-Hungarian Trieste in 1867, he lived here the last five years of his life.

He is buried in Trieste at the Anglican cemetery of Sant Anna, together with his wife Kate. A tidy, well kept, pyramidal grave stands to remind us of this great and largely forgotten intellectual.

Lever was born in Dublin in 1806 and educated in private schools. He got his degree in medicine at Trinity College, where his escapades became the plots for some of his novels, such as Charles O’Malley, Con Cregan and Lord Kilgobbin.

Before seriously embarking upon his medical studies, Lever visited Canada as an unqualified surgeon on an emigrant ship, and drew upon some of his experiences in Arthur O’Leary and Roland Cashel.

Once in Canada, he journeyed into the backwoods where he was affiliated to a tribe of Native Americans, but had to flee because his life was in danger, as later his character’s Bagenal Daly would be in The Knight of Gwynne.

While traveling in Germany, Lever met Goethe. Although as a dispensary doctor he was appointed to the Board of Health in County Clare, his conduct as a country physician soon earned him the censure of the authorities.

After years spent editing, writing, and entertaining relations with the most prominent intellectuals in Ireland, Lever set off to Europe in search of new inspiration. There he traveled by family coach stopping in different places for months at a time.

In Riedenburg, Germany, where he was renting a ducal manor, he had the privilege of entertaining Charles Dickens and his wife in August 1846.

Dickens would later publish Lever’s novel A Day’s Ride in his weekly journal All the Year Round, running parallel to Great Expectations from 1860 to 1861.

Lever continued his travels all over Italy. He used his experience and knowledge of Italy as the source for many articles and for the Italian sections of his novels.

According to Professor John McCourt, Lever was one of the most acute observers of the unification of Italy. His experiences also played a key role in forming his views about Ireland that continued to be the main interest of his fiction.

Eventually, Lever lost the joy he derived from composition. His innate sadness began to cloud the joyousness of his temperament. In 1867 depressed Lever was offered the lucrative consulship of Trieste.

The Austro-Hungarian town, which was at first “all that I could desire”, became “As to my new post, it is unpleasant, damnable. There is nothing to eat, nothing to drink, nothing to live in, no one to speak to. Liverpool, with Jews and blacklegs for gentlemen—voilà tout” (Downey 1906, II, 199).

He declared himself “very down in the mouth about my move. I feel as might a vicar leaving a snug parsonage to become bishop in the Cannibal Islands”, and “Of all the dreary places it has been my lot to sojourn in, this is the worst!” (some references to Trieste will be found in That Boy of Norcott’s, 1869).

In Trieste he rented Villa Gasteiger (current Vicolo degli Scaglioni 21/2, beyond Villa Marussig) on the top of the hill between Via Rossetti and Boschetto.

When Consul Lever first saw Villa Gasteiger, he was very disappointed.

“It is the most miserable little dog-hole for 150£ a year unfurnished in not only Trieste but in all Europe” (Lionel Stevenson p. 279).

Despite his grudges, Lever enjoyed an open view of the Adriatic sea from the mansion. The owner of the two-story villa was a municipal counsellor Edoardo Gasteiger, a prominent member of Trieste’s upper class.

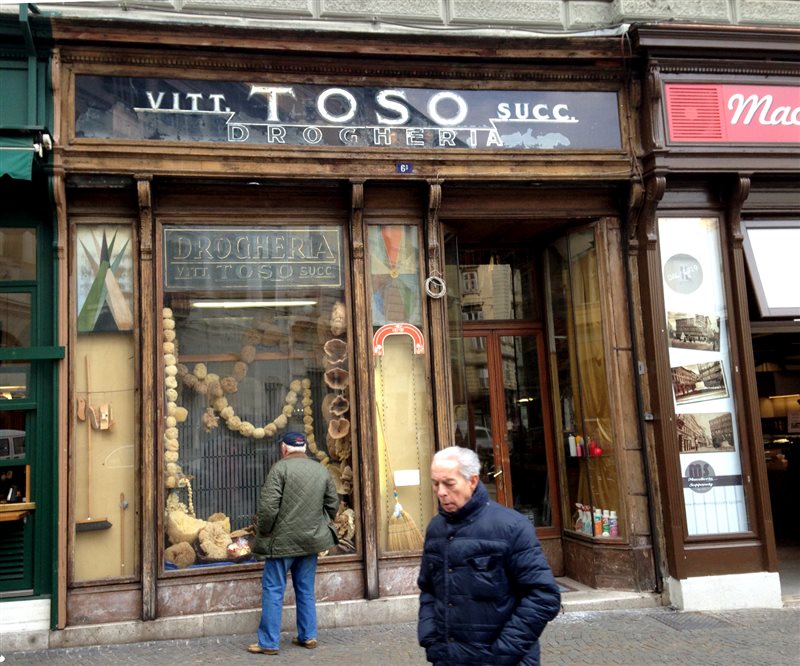

Like all wealthy families in Trieste, the Gasteigers had a profitable trading business. They imported natural sea sponges, for which Trieste was then the most important sorting port.

Nothing is left today of Villa Gasteiger demolished in 1967 to make room for apartment buildings. The sponge business, however, “Spugnificio Rosenfeld & Gasteiger” in Muggia, has incredibly survived to this day. Vintage samples of the famous sea sponges can be admired in the windows of Toso drugstore, one of the oldest shops in Trieste in Piazza San Giovanni 6.

Many were the British authorities and intellectuals who visited Lever in Trieste. They were all impressed by the beauty of the house, its luscious gardens and breathtaking views.

During the four years he lived there, he wrote The Bramleighs of Bishop’s Folly, That boy of Norcott’s, Lord Kilgobbin, and a short story for Saint Paul’s Magazine, then directed by friend Anthony Trollope.

Soon after, Lever, who hung on to his political relations in Ireland to be geographically reappointed, wrote to a friend:

“The Party, I fear, will go out before I can, and for all I see I shall die here; and certainly if they’re not pleasanter company after death than before it, the cemetery will be poor fun with the Triestini.” (Edmund Downey, vol. II, p. 227).

Instead Lever was surrounded by the many prominent British and Americans buried in Trieste.

Super post .

I was born in Trieste and live in Dublin , close to Lever’s original home .

The more marginal Triestine – Irish connection is Sir Richard Burton , who assumed the Consulate on Lever’s demise .

So glad to read something that does not focus on James Joyce and Trieste !

We visit Trieste from time to time ; not often enough .

I met a Dr. Cartala,MD. In the Year of 1980, in a Coffee House, in Denver Colorado