by Victor Caneva

It’s good to be a kid in Trieste. Depending on how their families celebrate, youngsters living here can participate in not one, not two, but three holiday celebrations that involve gift giving!

La Befana, the good-natured witch who delivers goodies to children on the eve of Epiphany, is not spotted in Trieste as often as in other parts of Italy, but the Triestini are not offended.

Trieste has the Festa di San Nicolò. And, like most things having to do with Trieste, the festa is uniquely Triestino while incorporating the milieu of cultural influences that have graced this great port city.

The Festa di San Nicolò, first and foremost, is a celebration of San Nicolò (or Saint Nicholas, the OG Santa Claus), born in Patara in modern day Turkey. Tradition holds that he was born into a wealthy, noble family and was orphaned at a young age. Later in life, he became the Bishop of Myra and may have taken part in the historic Council of Nicaea in 325 AD.

San Nicolò is most famous for an act of anonymous generosity, saving three impoverished sisters from being sold into prostitution by leaving bags of coins in their window under the cover of darkness. The benevolent bishop likely died in the year 343 AD – on December 6th – the day the Festa di San Nicolò is celebrated today.

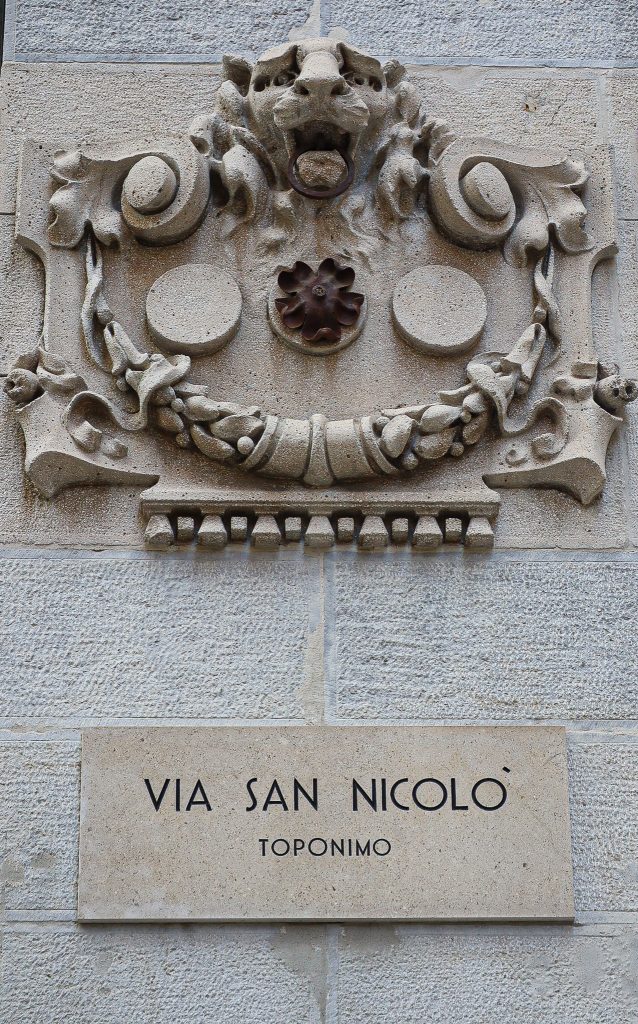

Arriving in greater numbers after Trieste was declared a free port in 1719, the city’s Greek population played no small role in its connection to San Nicolò. As the patron saint of seafarers, San Nicolò has long been revered by Greek sailors and merchants. When Trieste’s Greek Orthodox community constructed their first place of worship in the 1780’s, they dedicated the church to San Nicolò, christening it “The Church of San Nicolò and the Holy Trinity.” Today, the pedestrian Via San Nicolò runs from the southern edge of the church until it expires near the statue of Umberto Saba who, sadly, is always having his cane stolen.

As the preeminent holiday gift-giver for many Triestini families, some children await San Nicolò with even more expectation and joy than Santa Claus, his more modern, Northern-European alter ego who arrives later in the month. Leading up to the festival, youngsters write eager letters to the saint, requesting their most longed-after toys. Chocolate likenesses of San Nicolò are enjoyed by revelers of all ages. During the first week of December, the festive market stands of the Fiera di San Nicolò line Viale XX Settembre as they have since 1923.

In his 1945 article titled, “La Festa di S. Nicolò a Trieste,” distinguished Triestino anthropologist (among other accolades) Raffaello Battaglia, gives a heartfelt and incredibly informative account of the Triestine manifestation of the holiday. A jubilant day for kids through the ages, bambini Triestini would also write letters to the saint in times past while some children in the San Luigi neighborhood would even make their requests in person, happily shouting their desires to a statue believed to represent their patron saint.

Plates or shoes were left out on windowsills with the earnest hope that San Nicolò would fill these vessels with gifts on the night of December 5th, as he made his nocturnal trek through Trieste, sometimes accompanied by a donkey laden with presents.

Before it moved to Viale XX Settembre, the traditional holiday market known as the Fiera di San Nicolò ran from the Piazza della Repubblica to Piazza Goldoni and up some intersecting lanes. Warmly lit stalls and storefronts, many displaying affordable toys and treats for youngsters, filled Triestini children with wonder. It was a day, especially for kids who were not fortunate enough to receive gifts or sweets often, to indulge and experience the magic of childhood.

There are varying theories on how the Festa di San Nicolò originated in Trieste. Some posit that the festival is celebrated here because of Trieste’s historical link to Austria, where the holiday is also celebrated, but with significant differences. Others point to the influence of Trieste’s Greek community, who undoubtedly imported their own customs concerning San Nicolò.

Intriguingly, Battaglia argues that communities in Istria, just to the south of Trieste, may have been the progenitors of the tradition. Some coastal Istrian towns are known to celebrate the festival in similar fashion and have a longstanding history of venerating the patron saint of seafarers. In fact, a church in Parenzo (Poreč), Croatia, was dedicated to San Nicolò as early as the 8th century.

However the Festa di San Nicolò originated, two things are certain. One is that Trieste has a beautiful knack from absorbing influences from other places and making them unmistakably her own. And secondly, the children of Trieste are extremely fortunate to enjoy a holiday where they are so richly celebrated.