words and photography: Alessandra Ressa

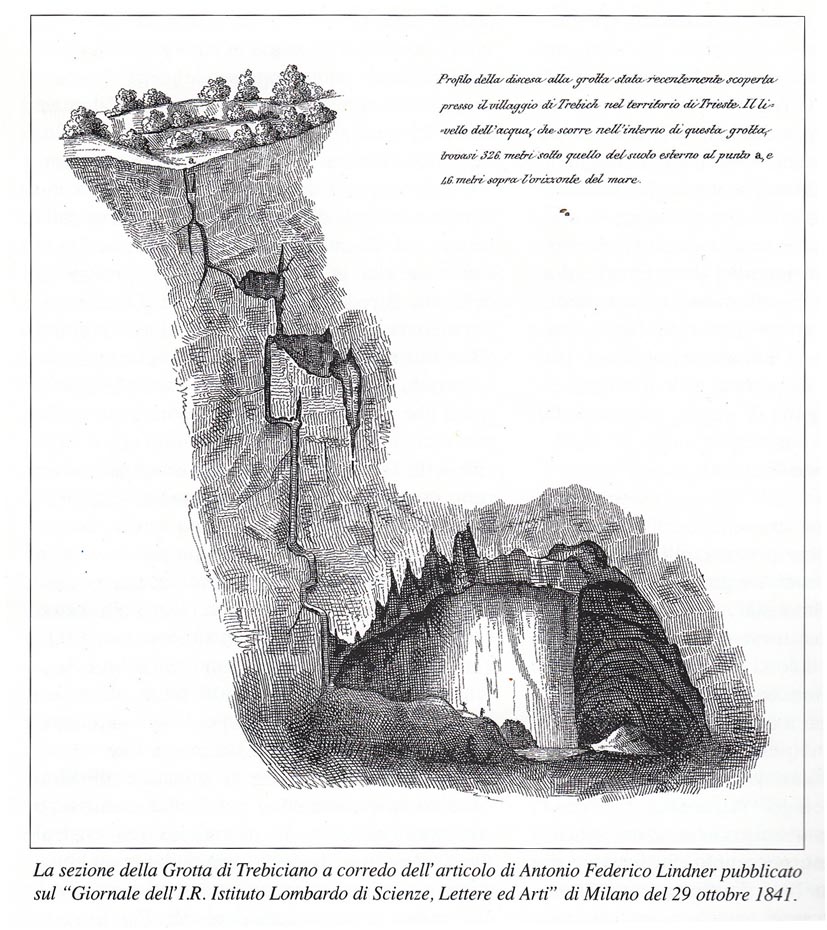

Considered for almost a century the deepest cave on Earth, with its 340 meters drop of vertical, narrow pits, the Trebiciano Abyss is the result of the incredible perseverance of a Triestino engineer and explorer of Viennese descent, Anton Fredrick Lindner.

In 1841, on an almost personal mission to provide the city with drinking water, Lindner managed to connect Trieste’s Carso to its underground river Timavo, thus laying the foundation of modern speleology. “No step is taken without a man being exposed to the worst of dangers, should courage or strength abandon him” the resilient explorer wrote during the challenging underground excavations to find the river.

Once found, however, the waters were judged to be too deep in the bowels of the Earth to be exploited, and the local administration soon suspended financial support for the project. But it was too late for Lindner, his quests had undermined his health and finances. He died of tuberculosis at the age of 40.

Today, the Abyss is a natural wonder and longed-for destination of expert spelunkers, scientists and cave explorers. It is also one of the most efficient technological laboratories for underground research. But most of all, it is the keeper of many geological mysteries that have yet to be unveiled.

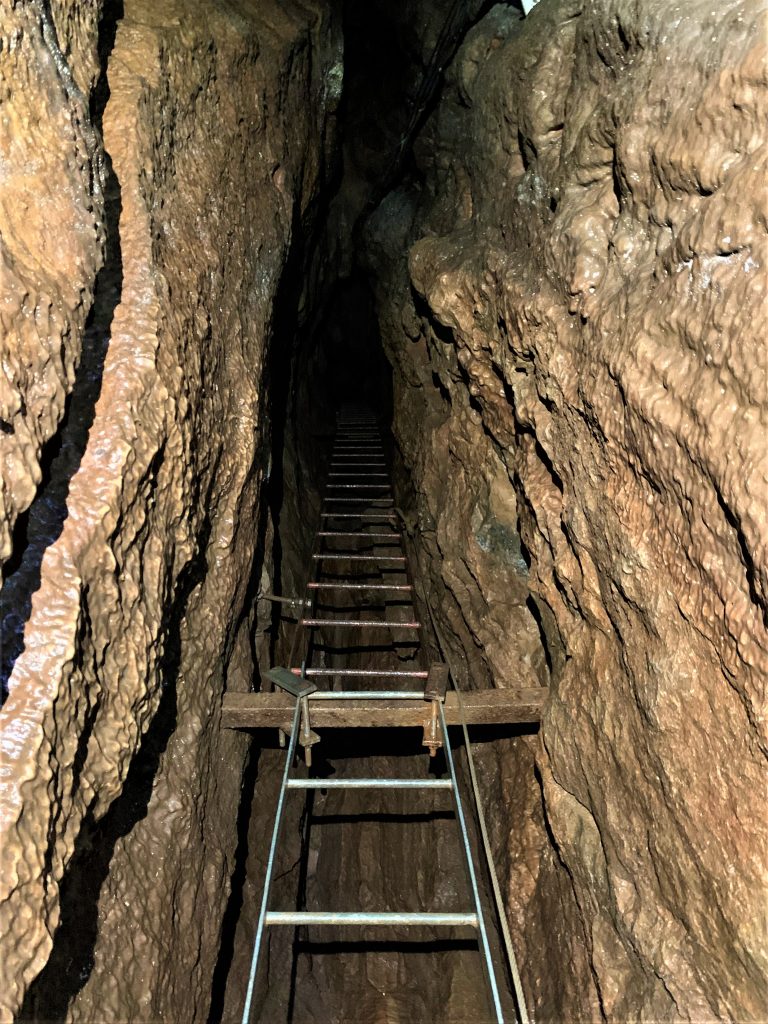

More than a thousand precarious-looking steps along an endless sequence of perfectly vertical metal ladders, some rusty, some embedded in the mineral deposits of the ever dripping water from above, others new and shiny, separate the sunlight of the Trebiciano woods from the absolute darkness of the bottom below. The perpetual upgrade and replacement of climbing equipment has been managed for decades by the tireless speleologists of Società Adriatica di Speleologia, one of the oldest in town. Part of the job is also the management of the hypogeum station, not far from the entrance to the abyss, where scientists monitor, among other things, the water level and flow of the underground river.

Visiting the Trebiciano Abyss is not for everyone. You need to be an expert speleologist and be reasonably fit. You also need proper equipment to secure yourself to the ladders and the metal wires that run along them. The entrance to the Abyss is carefully hidden inside a tiny house at the bottom of a Karstic depression (dolina) in the woods. The door of the building is kept locked at all times.

Once inside, a neatly tiled floor frames a spooky trapdoor. This is the entrance to the center of the Earth. Friend and expert SAS speleologist Giorgio Zanutto leads the way, after activating a closed-circuit phone connected to a communication station about 50 meters below. That’s because mobile phones don’t work. At least until you reach the bottom.

If nearly 340 meters of bottomless, narrow, vertical pits grasping on to narrow ladders do nothing to shake your self-control, wait until you reach the Bridge of Fear. This structure, made of narrow, thin metal sheets suspended into the darkness deserves its gloomy name. But if you get to that point, you’ve gone too far to turn back.

The feeling of elation when I finally reach the bottom and step over the white, thin sand deposited by the Timavo river flood after flood is difficult to describe. The darkness, the deafening silence, the tiny dust particles floating thickly in the air make me believe, only for a moment, that there is no gravity. I can sense I am surrounded by a cave of enormous size but even my most powerful flashlight beam cannot show its boundaries. It feels like being on another planet. I cannot help but think of the Moon landing. And how Lindner must have felt when this incredibly large cave named after him opened beneath his feet.

As soon as I sit and grab an energy bar to regain my strength the side pocket of my muddy jumpsuit begins to vibrate. It’s my mobile phone receiving tons of text messages on WhatsApp. The recently installed Wi-Fi works wonders 340 meters below the ground! And that, like everything else down here, is truly amazing. My friend Giorgio is restless, he wants to show me everything. But all I can think of is if I will ever make it back up. I just want to lie down and sleep and wake up in my bed. I reluctantly follow him.

I have come all this way down, I simply must see the river and touch its cool waters. First, I have to climb on hands and knees enormous sand dunes peppered with big fat centipedes, then the dunes turn into huge, weird, slippery, Swiss-cheese like rocks, which, at some point in the past millennia, fell from the ceiling of the cave. And, at last, the flowing waters of the Timavo! Clear, cool, and incredibly silent. My eyes fill with tears. But Giorgio doesn’t notice, he keeps going forward, and I can’t fall too much behind because it becomes impossible to find my way around among the huge rocks in the thick darkness.

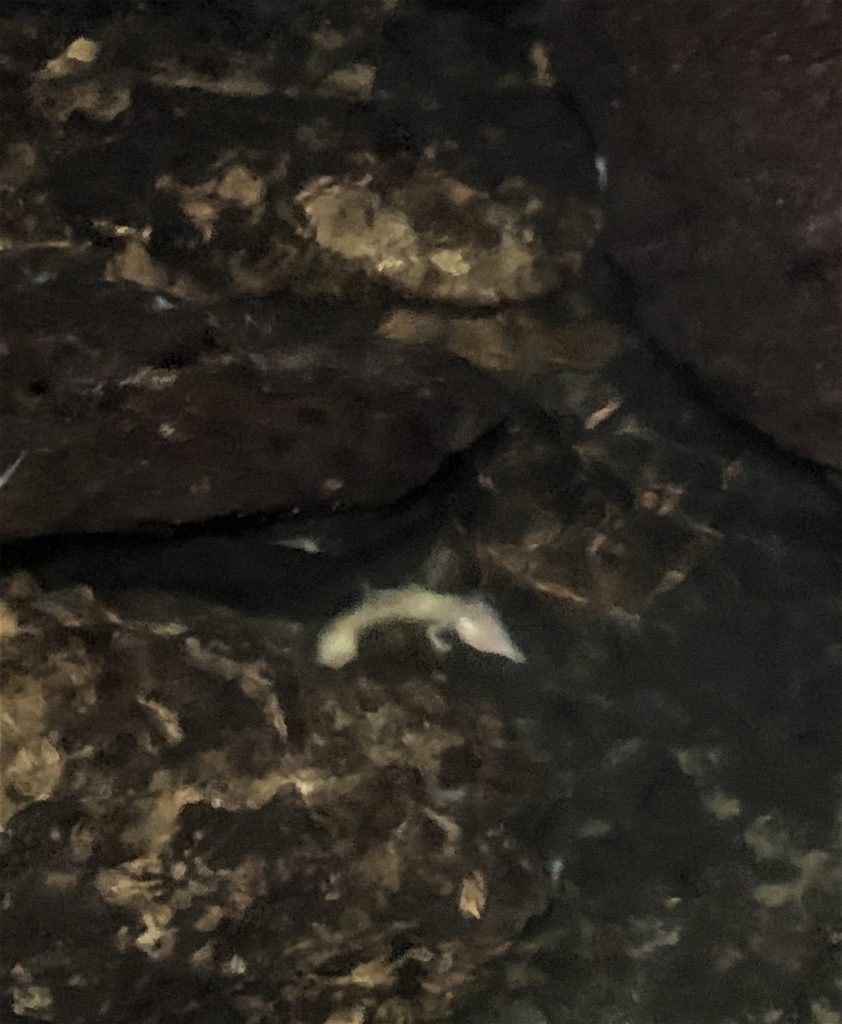

Seeing my first olm (Proteus) in the wild makes me soon forget all about the upward climb ahead. This tiny, eyeless, shy, pale pink creature sitting in shallow waters is motionlessly staring at equally eyeless white shrimp all around. I see not one olm, but many.

The echo of the enormous cave is so powerful that even the tiniest drop of water falling from the ceiling amplifies the noise to the point that you get constantly startled. Sometimes you are certain that someone dropped a big rock into the water right next to you, other times you capture a sigh, a movement, a voice… It feels like minutes but the hours pass quickly when you are underground, and it’s time for the last Herculean task: the vertical climb back up. Like an eager horse heading back to its stable after a long working day, I grab the first of the many ladders and off I go. Surprisingly, the way up is a lot easier than expected. Strange sites, objects and rocks and difficult passages I encountered on the way down now look familiar and actually reassuring, as if encouraging me to proceed. In addition to that, some good personal conversation with my fellow speleologist and a bit of duet opera singing brings me all the way back to the trapdoor in no time. It’s done, I’ve been to the center of the Earth, and back to tell.

The explorations of the site are not over yet. While another, huge cave where the river continues its underground race to the sea has been recently discovered by a French expedition, local and international teams of experienced speleologists are currently researching further entrances. Following Lindner’s steps, they believe that more caves along the river are yet to be found. For further information on the Trebiciano Abyss, consult www.sastrieste.it.

Best compliments to the Italian-Scottish “explosive combination girl” on her curriculum vitae.

A resume rich in experiences and knowledge.

Beautiful article! Thank you.