by Alessandra Ressa

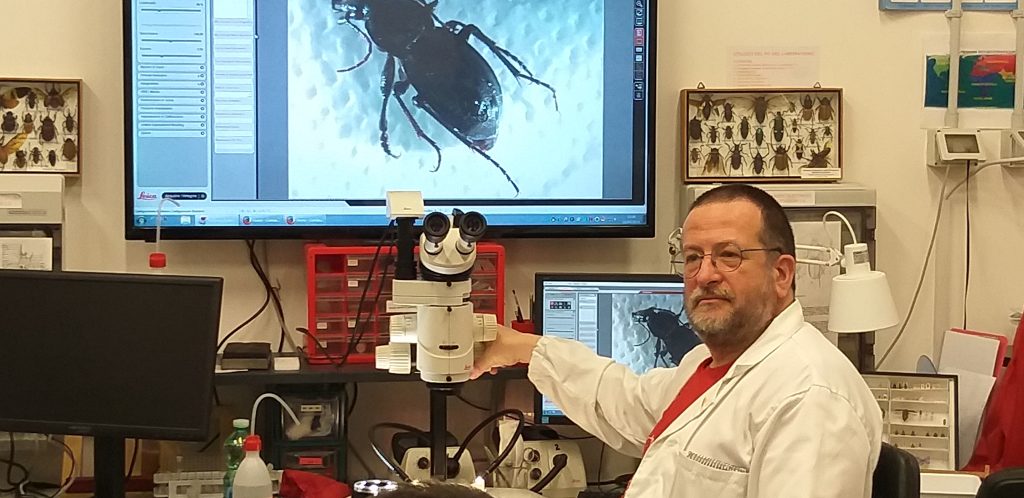

He is probably the best entomologist in Trieste, and one of the most knowledgeable scientists nationwide in the field of insects. He will gladly provide an exhaustive answer to anything you wish to know about creepy crawlies and throughout his career has discovered many tiny creatures, some of which now bear his name. He has the rare gift of making you appreciate bugs and even love them, no matter how horrid you think they are. He lives in a cabin in the woods in his beloved Carso, surrounded by what he loves best: wilderness. Meet Andrea Colla, entomologist at the Museum of Natural History of Trieste and expert naturalist, botanist and spellonker.

How did your passion for insects begin?

I owe it all to my father, who was an expert rock climber, speleologist and nature lover. When I was a child, he never took me to the cinema, nor for strolls in Piazza Unità or Barcola. He took me with him along hikes in Carso, or pushed me into caves. Every weekend we would ride his Lambretta at crack of dawn and reach the vast, green, almost unspoiled Trieste hills to explore the beauty of nature that surrounded us. As my curiosity as a youth normally concentrated on living creatures, I soon began to observe insects, the most abundant and easy-reach wildlife available. I greatly enjoyed removing horseflies from my grandpa’s grateful donkey, and observe their huge eyes and mandibles. When my father judged me old enough, he took me into caves, then accessible only through means of home-made wire and wood ladders. The fantastic, legendary creatures which populated the underworld and the illustrated books I devoured at night became real. Rare olms, eyeless white bugs hiding under rocks and rotting wood in the depths of Carso, a magnificent white world made of tiny legs and long antennae was unveiled in front of my hungry eyes under the scrutiny of my flashlight and magnifying glass. I was five or six years old. There and then I realized how much I loved all this, and how important it was to share it with others, in museums, where other children like me could feed their hunger for knowledge. Since then, my career as a scientist and researcher has been devoted to providing answers to all the questions about nature I had as a child. And, the more you answer questions, the more questions you have.

How long have you worked at the Museum of Natural History in Trieste and what have your contributions been so far?

My career as an entomologist at the Museum began approximately 25 years ago. It started with the careful inventory of old, precious collections of rare insects to make accessible to the public, it then evolved into the creation of a fully-equipped laboratory where to study insects. The lab has now developed further, and is being used by all scientists at the museum. We not only look at the microscope-enlarged stomach of the rare cave Leptodirus to determine what it had for breakfast, but examine dinosaur remains and much more. I am proud to say that many a scientific breakthroughs came from our lab. Another, unique, feature of the museum that I am proud to have contributed to is the room dedicated to cave creatures and their environment.

For the second time in less than 15 years the museum will be moved to a new location, from decentralized via Cumano to beautiful Porto Vecchio. How do you feel about it?

Although I dread to think of another move -you can only imagine the amount of stuff to be packed, unpacked and reorganized, and the time it will take for the museum to be once again accessible to the public- I can only rejoice at the chance of the prestigious relocation to Magazzino 26, in Porto Vecchio. Bigger rooms, bigger storage, more centralized position… they can only mean more exhibit areas where valueless stored collections will finally see the light, and consequently more visitors. Of course, I hope and will do my best to ensure that the new museum will not just be about exhibits, but also about scientific research. I can’t hide I have great expectations, it may possibly become the number one museum in town!

How many new species of insects have you discovered? Do you have a favourite bug?

I have discovered about 12 new amazing species so far, some bear my name or something similar to it, such as the Pretneia collai, others I have named after the location, such as the tiny cave predator Montis matajuris. This last is probably my favorite, a small cave beetle I discovered while conducting explorations with my father. Another very interesting, rare and rather minuscule insect I discovered is the Disparrhopalites tergestinus, with its long antennae and peculiarly round body.

What can you tell us about the recent debate to introduce insects as staple food in our diets? Italians have shown particular aversion to the idea.

I am carrying out extensive research on this controversial topic. We need to remember that the statement that insects as food is something experimental and new for humans and therefore more at risk of allergies and less digestible is false. Many populations around the world have been feeding on insects for centuries and there is no evidence that their dietary habits are harmful. For example, insects contain chitin, which is also consistently present in mushrooms, widely consumed by Italians. Interestingly, human bodies contain the chitinase enzyme. In addition, producing food from insects has far less impact on the environment than traditional meat. Insects eat much less than vertebrates because they don’t have warm blood, so in proportion the amount of meat they provide is much bigger. Some evidence supports the possibility that eating insects may have had an important role in the development of the brain in Homo sapiens, because of its heavy protein content.

How have the Carso and its wildlife changed since you were a child?

Unfortunately, they have changed a lot, and not for the better…The amount and variety of animals, and especially insects, which populated the Carso of my childhood has enormously reduced in numbers. Today, the quantity of insects I can observe in a month of careful exploration I could see in a day when I was younger. Many experts, including myself, believe that biodiversity is decreasing because of climate change. Our Carso used to have a cool and humid environment, while it tends to be now hotter and drier. As the process is happening quickly, local plants and animals don’t have time to adapt, and are thus disappearing, to be replaced by more generic, “globalized” species, or, more often than not, by nothing at all. People who have no knowledge of nature can claim that there is no climate change. Although it is true that climate appears to have changed constantly during the evolution of the planet, what is worrying about the change we are now witnessing is the speed at which it is happening, and this is surely caused by humans. We need to bear in mind that when changes are not gradual, nature cannot adapt, and neither can man. Not only we risk to lose our biodiversity in Carso, but we risk to lose its entire life.

What can be done?

At this point, it is impossible to stop the process. What we can attempt to do is to slow it down to contain damages. For example, the devastating fires which hit many areas of Carso last summer and contributed to its desertification could have been prevented, so prevention is one of the answers. Another essential action we can take is raise awareness through education in order to teach people how to take care of the environment. An important part of my profession has been dedicated in the field to this in particular, to educate people to know, love and respect the environment.