By Victor Caneva

The second Wednesday of June was a soggy, gray affair in Trieste. I wasn’t afraid of the rain, but my camera was a little skittish, so I decided to postpone. Switching up the normal program, I invited my dad along and we headed for Parco San Giovanni on a sunny Sunday afternoon.

My first exposure to Parco San Giovanni came from pictures I stumbled upon while researching Trieste. The historic yellow buildings surrounded by flowers, including a rose garden, were inviting and the description of the park, which translated into something like “Former Mental Institution” was gripping to say the least. I remembered seeing a BBC article about Trieste’s revolutionary mental health model, spearheaded at the Psychiatric Hospital of Trieste – but to be honest, I skimmed far too quickly to retain any useful information. I ignorantly pegged Parco San Giovanni as a nice place to see flowers and old buildings. After visiting, I would learn this was quite an inadequate way to think of the park.

We headed out from the center of the city in the general direction of Ospedale Maggiore. After turning on via dei Porta, which conquers the hill leading up to San Luigi at an almost unbelievable angle, we were treated to a novel perspective of Castello Miramare, barely peeking out from behind Scorcola with Castello di Duino resting right above it. When we finished panting, we descended through Parco Farneto into the rione of San Giovanni.

Soon we arrived at the entrance to Parco San Giovanni. As we passed through the open gate, my first reaction was confusion. There was much more vehicular traffic winding up the hill leading further into the park than I expected on a Sunday afternoon. Signs for active health services, mental health facilities, and university buildings quickly informed me that I had not simply arrived at a traditional “park.”

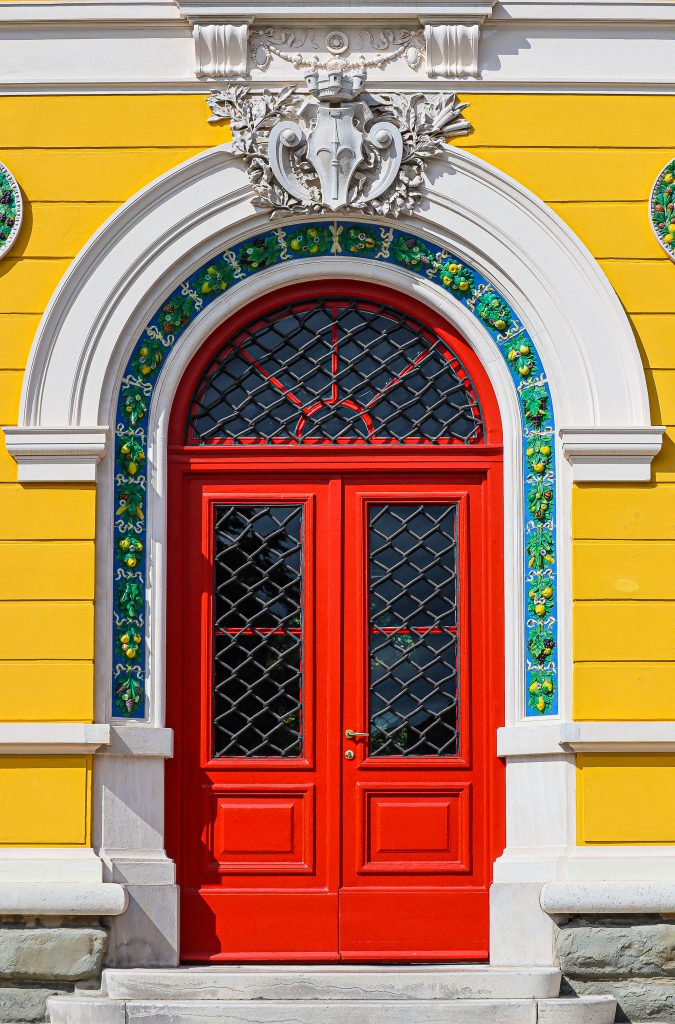

I turned left on a footpath and cruised through pleasant gardens in front of a creamy yellow building that looks like an old villa, but is now a health services property. We continued uphill, waiting for the “park” section to start. Apart from the buttery hues of the buildings, many of which were either built at the turn of the twentieth century or constructed to match the style of the original structures, Parco San Giovanni felt incongruent to me. We certainly enjoyed stately gardens and plenty of vibrant blossoms, but they were interspersed with parking lots, public buildings, parts of a university campus, and even the Museum of the Antarctic. At times I wondered if I was trespassing on state property, but this incertitude did not plague the locals at all. Children were happily playing in front of the Franco e Franca Basaglia Theater and families were strolling between health offices and abandoned sanitarium wards.

Parco San Giovanni did not fit my narrow definition of a park, but the answer to my puzzlement was emblazoned in red on one of the golden buildings, La Liberta E Terapeutica, or Freedom is Therapeutic. In the 1970’s, the Psychiatric Hospital of Trieste was the epicenter of a revolution in the philosophy and practice of psychiatric care. This radical shift of methodology was pioneered by celebrated psychiatrist Franco Basaglia, who pronounced, “It is impossible to have therapy in a place of seclusion, in a place where people are oppressed. You must ensure liberty and freedom in the beginning and then work with the person as an equal, on an equal basis.”

From it’s inauguration in 1908, like many sanitariums around the world, the Psychiatric Hospital of Trieste was a place where the mentally ill were sequestered from the rest of society. Patients were institutionalized and deprived of personal freedoms. When Basaglia arrived at the facility in 1971, there were 1,182 people housed at the facility, about 90% of whom had been admitted forcibly. Basaglia ardently campaigned for the dismantlement of thisl model, believing cold institutions were not only counterproductive to curing mental ailments, but even contributed to them. His team first worked to transform the culture of the hospital, advocating for the humane treatment of residents, opening wards, and ceasing shock therapies and physical restraint. Staff were no longer simple caretakers, but partners with the patients in the therapeutic process.

In 1973, Basaglia’s team engaged in outreach to begin breaking down the separation of the hospital from the community of Trieste. They worked with city organizations to host concerts and cultural events on the grounds and commissioned the sculpture of Marco Cavallo, a blue horse representative of the patients’ desire for freedom. In a landmark victory for Basaglia and his adherents, a law was passed in 1978 allowing for the abolishment of psychiatric hospitals and the formation of other therapeutic models. In 1980, the Psychiatric Hospital of Trieste ceased operations and soon thereafter, Basaglia died. Today, 24/7 mental health centers spread throughout the province provide care to those in need using the inclusive philosophy pioneered in Trieste. About 70 patients still reside in Parco San Giovanni.

One could argue that Parco San Giovanni’s eclectic makeup, with gardens, schools, retirement homes and mental health offices is the physical outworking of Basaglia’s philosophy of freedom. It is a place that was born in exclusivity transformed into an example of inclusivity. It may not be the most straightforward “park,” but it is a shining example of the healing that can come from treating others with dignity.

Oh yes… The magnificent rose garden, one of the largest in Europe, is perched in the upper reaches of the park, featuring almost 5,000 varieties of roses from all over the world. So I wasn’t all wrong. Parco San Giovanni is “a nice place to see flowers and old buildings.”