By Alessandra Ressa

There is a street missing a number in the residential neighborhood of San Vito, in Trieste.

Although many of the elegant old villas in the area have been replaced by luxury apartment buildings, and you may be induced to think the numbers might have been redistributed in a non-consecutive manner, in via Bellosguardo the number 8 is actually missing.

In that lot there once stood a beautiful mansion which belonged to the Arnsteins, a rich Jewish family.

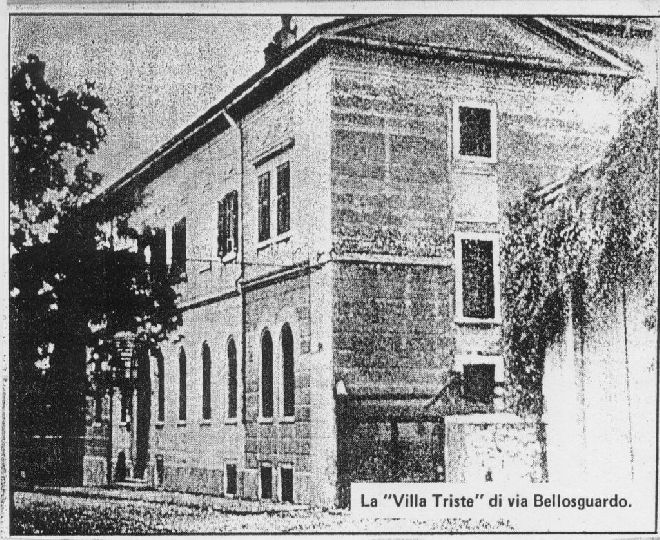

During World War II it became known as Villa Trieste: a place of torture, agony and death. When their home took on that infamous reputation, the Arnsteins had already escaped to America.

This is one of the sad stories of Trieste that followed Mussolini’s racial laws, announced by the fascist leader in front of an immense cheering crowd in Piazza Unità in 1938.

Villa Arnstein, located in via Bellosguardo 8, was confiscated by the fascist government in 1940. From 1942 to 1945 it served as the office of the ill-famed Special Inspectorate for Public Security.

It was the first such office to be opened by the Ministry of Home Affairs on the Italian territory. Many more were to follow all over Italy, all of them with the same terrifying reputation.

It was enough to mention via Bellosguardo to send cold shivers down one’s spine. Infamously known as the first Villa Triste (house of sorrows), the mansion became a place where people were tortured and killed in the hands of the fascist regime with the compliance of the SS.

The villa was manned by a special fascist militia, from different corps, such as the police, carabinieri, financial police (Guardia di Finanza) and the army. It was the first of 21 such places all over Italy.

The inspectorate, headed by the detective in chief Giuseppe Gueli, soon became headquarters to the ill-famed Collotti Gang– a group of ruthless fascist militiamen that terrorized the city with acts of systematic violence, torture and death.

Women and children weren’t spared. Their leader, 22-year old Gaetano Collotti, was a policeman whose “legitimate” powers allowed his gangsters to commit numberless atrocities. The purpose of the inspectorate was to suppress any propaganda or anti-fascist activity.

It was organized in groups of armed men, each numbering 50 militants. The initial victims of the vicious gang were predominantly Slovenian anti-fascists and partisans, but soon, once the Nazi took control in 1943, Collotti and his men actively contributed to arrests and deportations of Trieste’s Jews. During arrests, the victims were robbed of all valuables, which were later distributed among the gang members.

According to Trieste historian Claudia Cernigoi and to many witnesses at the trial following liberation for the atrocities committed by the inspectorate, it wasn’t hard for the Collotti gang to find Jews in hiding.

In exchange for money and favors (10,000 lire for each Jew reported – a fortune then), hundreds of willing Triestini reported on their Jewish friends and neighbors. Jews were arrested, tortured and forced to confess names and hideouts of family and friends.

While Trieste Jews who survived the beatings were often handed over to Nazi authorities for deportation, Slovenian partisans and antifascists were subjected to abominable tortures. Official documents filed at the trial described many such agonies.

To obtain information, the fascist police broke feet, pulled fingernails, and broke hands indoors. They burnt men’s testicles with hot irons, women’s breasts with cigarettes. Captives were electrocuted, pregnant women kicked in the belly. Many rapes were also reported, some of the victims barely teenagers. One of the most recurrent tortures was called “the bench”: the prisoner was tied and large amounts of hot water were poured through a hose in the mouth. The stomach would fill up with liquid that was then compressed violently so that water came out of mouth and nose, sometimes even through the ears, according to witnesses, thus preventing the victim from breathing. Death by drowning often followed.

Others were hanged by the neck with only their toes touching the ground. Weakness or sleep provoked immediate strangulation. Those who survived the tortures were transferred for further mistreatments to the concentration and extermination camp inside the former rice mill of San Sabba, the only Italian concentration camp in Italy to have a crematorium, just a couple of kilometers from via Bellosguardo. From San Sabba many captives were deported and found their death in the camps of Mauthausen (Austria) and Dachau (Germany).

In order to prevent the residents who lived around via Bellosguardo from hearing the victims’ desperate and ceaseless cries, the fascists and the SS played loud military marches through gramophones installed in the house. Speakers propagated the music day and night.

This however did not prevent the site from retaining its infamous reputation as a place of terror and death as screams could be heard for blocks. It emerged from testimonies at the trial that most residents, not only in San Vito but all over town, were aware of the brutal activities of the inspectorate in via Bellosguardo.

However the climate of hate, suspicion and fear that characterized those dark years of Trieste was such that most people chose to mind their own businesses or collaborate. Shortly after Trieste was liberated, Villa Triste was demolished. Some say it was to erase proof of atrocities committed by the Italian fascism.

At the end of the war, to avoid being judged by the criminal court, Gaetano Colotti managed to escape Trieste with his pregnant girlfriend and some of his militiamen. He was at the wheel of a truck filled with silverware, jewels, furs and other precious goods, undoubtedly the spoils of the people he arrested, when the truck was intercepted and stopped by a group of partisans in Carbonera, near Treviso.

He was immediately recognized and executed on the spot together with his girlfriend. Other members of the inspectorate were tried and condemned to years in prison, but later released as Trieste tried to wash through oblivion that indelible stain of active collaborationism.

To add shame upon shame, in 1954, Gaetano Collotti inexplicably received a posthumous bronze badge of honor by the Italian government for presumed anti-partisan activity near Tolmin, today in Slovenia, in 1943. Protests followed in what was believed to be a great injustice towards the victims of via Bellosguardo. The Ministry replied then that once a military badge is issued, it is not possible to revoke it – an example of Italian bureaucracy at its worst.

In via Bellosguardo today only a small, barely visible bronze plaque remains at the corner where Villa Triste stood to remind you of the horrors. Like with all places connecting collaborator Triestini with the atrocities committed during World War II, the city appeared to be wanting to forget that uncomfortable past.

Rather than preserving the site for future generations as testimony of the darkest moments in Italian history not to be repeated, or even proceed to restitution of the property to its legitimate owners, the city preferred to erase every trace of Villa Triste and sold it to private realtors, who, in the late 1960s, built luxury apartments on Villa Arnstein’s ashes.

The one in via Bellosguardo wasn’t, however, the only Villa Triste in town. In central via Cologna 6, next to Trieste’s Giardino Pubblico, there was another site of horror and death operated by the Collotti gang.

Used as a Carabinieri station after the war, the building in via Cologna was then abandoned for years, only a blackened sign at its entrance and a dried-out wreath reminding passers-by of its dark past.

Although many residents signed a petition to rehabilitate it and convert it into a museum, it was eventually sold to private realtors just two years ago, then entirely renovated and converted into private apartments, still on sale today. The inhuman prison cells in the basement, with their past of unimaginable suffering and death, have been transformed into garages and modern cellars to store skis, bicycles and strollers.

Incredibly, notwithstanding the initial attempts to demolish it entirely right after the war, part of the concentration camp in San Sabba (Risiera di San Sabba) is still standing today and open to visitors.

It is a gloomy, tall brick building ironically surrounded by supermarkets and other huge commercial lots. Every year, on 27th January, International Holocaust Remembrance Day, a ceremony takes place there to commemorate all victims of Nazi-fascism.

Thank you Alessandra

We can’t forget what appened .. HERE

We need to read articles like this one

Thanks for that. Very interesting and I had no idea!

Very good and informative article. Bravo.

Thank you for this painful but important information.

Visiting Trieste from Sacramento the city is beautiful and vibrant, your article has given me a feeling of what it was like here at that time.