by Alessandra Ressa

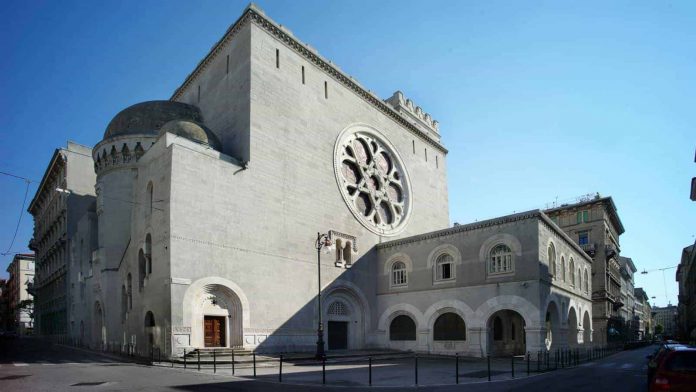

Trieste’s history is firmly intertwined with its Jewish community that greatly contributed to the city’s economic and cultural growth for centuries. The great Synagogue in via San Francesco is one of the biggest and most impressive temples in Europe, and it is a clear reminder of the cultural importance and influence of the Jewish community in Trieste, especially during the Austro-Hungarian empire.

Even before the great Synagogue was built and despite the discrimination by the local authorities throughout the history, Jewish Trieste had been thriving for centuries while the Austrians were in power. The areas behind Cavana and Piazza Unità, designated more than three hundred years ago to be the town’s ghettos, are still fascinating today, with their narrow, dark alleys, taverns and antique shops.

The earliest document to mention a Jewish settlement in Trieste dates back to 1236. It was a notarial deed which mentioned a city Jew, Daniel David, who had spent 500 marks to fight bandits in Carso.

From 15th century on Jews from Germanic territories began to settle in Trieste. In the Middle Ages, they mainly held small commercial activities and worked as money lenders. During the 17th century the Jewish people of Trieste, just like most Jewish communities around Europe, had to fight a battle against local authorities, who wanted to geographically contain the community into ghettos and isolate it from the rest of the population.

Thus, in 1693, Habsburg emperor Leopold I forced the Jews of Trieste into the first ghetto, an area near Cavana known as Corte Trauner, a tiny square surrounded by narrow alleys which was easy to contain and isolate from the rest of the city.

Bearing the name of an influential Triestine family, this small square surrounded by eight apartment buildings was chosen as the first location for the ghetto. Because of its size, entire families had to live in crammed conditions, two families often having to share a room. The only water came from a well in the middle of the square.

The Jewish community protested, asking for a larger, more central area. As incredible as it may sound today, Piazzetta Trauner, in the heart of Trieste’s historical center, was then considered decentralized and therefore not good for business.

Three years later, in 1696, the ghetto was moved to an area known as Riborgo, behind piazza della Borsa and piazza Unità. The area included the districts of Malcanton, Riborgo and Beccherie. Those were the three main streets, intersected by dozens of tiny alleys such as via del Pane, via delle Ombrelle and via Stretta. One of the main pathways to ghetto was through Passo della Portizza, a tunnel-like passage from piazza della Borsa. This area of town became the Jewish ghetto for the centuries to come. It was vacated and partly demolished during the fascist regime in 1937.

The detailed history of the ghettos is available on the website of the Jewish community of Trieste (www.triestebraica.it). Starting from 1696 the area became the commercial heart of the city. It was surrounded by a tall wall and had three entrances (in piazza del Rosario, at the end of via delle Beccherie and Riborgo).

The doors were guarded by Christian officers, whose task was to keep them closed from dusk till dawn. In 1748 the first synagogue and school were built, but, in 1784 the doors of the ghetto opened indefinitely. Emperor Josef II issued “Tolerance licenses”, which allowed Trieste Jews to circulate freely.

A year later segregation was abolished. Most part of the Jewish community however decided to live and work in the ghetto, where two more synagogues and schools were built. The fourth synagogue was opened a few years later in via del Monte, outside the ghetto near Corso Italia, a clear sign of the growth of the community. In those years Trieste became the home to many Jews from the towns and villages of the then Republic of Venezia, which included vast areas of Friuli Venezia Giulia.

The area became the busiest in town. The shops were closed on Saturdays, but were open on Sundays. Non Jewish Triestini enjoyed shopping there, you could often catch them bargaining for antiques and bric-a-bracs. Unfortunately, the whole area was devastated by massive demolition of large parts of the old town put forward by the fascist regime in 1937.

All the synagogues, with the exception of the great one in via San Francesco, were demolished, and nothing has remained today of the religious life of the ghetto. Luckily, some of the religious objects inside the synagogues were saved and are now exposed at the Museum Vera and Carlo Wagner, in via del Monte 7, next to Trieste’s Jewish school (www.museoebraicotrieste.it). Many blocks of the fascinating old Jewish quarters are gone forever, but the area has nevertheless retained its magical atmosphere of the past.

A stroll in the old ghetto is a dive into the past. You can still find good bargains in the many antique shops, some of them are real mazes made of room after room of old furniture and curious objects. Others sell used books. Finding precious, rare editions is not impossible if you have some time. Some of these shops still belong to the descendants of those same Jewish families who lit up the ghetto three hundred years ago. On sunny days, the merchandise is often placed outside the crammed shops making the narrow lanes lively like they must have been in the old times.

The Jewish ghetto is not only the best place in Trieste for antiques, but some of the city’s best restaurants and osteria are located here, offering visitors a charming, secluded atmosphere. Among the oldest, very popular spots is Osteria da Marino in via del Ponte, which has miraculously survived for almost 100 years without ever losing one bit of its popularity for wine and foods.

Opened in 1925, it was bought by Marino in 1940 and soon became a popular meeting place for university students. Since then, its atmosphere and clientele have remained the same. Before the production became illegal for its high level of sugars, they also served the best fragolino wine in town.

Along the same narrow lane where Osteria da Marino stands, until the early 1970s used to be a Kosher butcher’s shop. Due to the influence of the Jewish community (there were over 6,000 Jews in Trieste in 1938) eating kosher was quite common in Trieste.

As British writer Jan Morris wrote in her book Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere, Kosher food was even served at Antico Caffè San Marco. Today, there are no kosher restaurants in or outside the ghetto and you can only buy Kosher food at the great Synagogue’s market if you are a member of the community. There is, however, an itinerant food stand that only serves Kosher dishes named Glam Casher. Although it has been in business since last month, it has become so popular that its owner, a retired Trieste lady from the Jewish community, is busy selling her food all over the region. If you are lucky, you may see her stand in the ghetto.

I plan on spending one day in Trieste in May from Venice, What’s the best way to do this. Thank you, I’m really looking forward to it. Howard Rottenberg